After a season which has seen Neymar establish himself as a vital member of Barcelona’s team, many pundits, not least in Brazil, are now expecting the prodigy to realise his long-standing potential and challenge Messi – as well as Real Madrid rival Cristiano Ronaldo – for the position of best player on the planet. As Life Beyond Sport waits patiently for the prodigal son to turn up to the interview, we’re told by his friends that, Neymar is modest, deeply religious, devoted to his family, particularly his father and his four-year-old son, and dedicated to his team-mates.

We’re told that Neymar thinks nothing of money or personal glory, and is quick to forgive those who trespass against him. For example, Juan Camilo Zúñiga, the Colombian whose knee fractured a vertebra in Neymar’s spine in this summer’s World Cup quarter-final in Brazil. A nation wept, its hero and talisman was ruled out of the competition, and there was even a fear that he might be permanently paralysed. More than a personal setback, it was seen by Brazilians as a national tragedy.

Before he was bought by Barcelona for between £44 and £67 million, depending on which report you believe, Neymar played for Santos – the old team of the legendary Pelé. He made his professional debut at 17 and straight away was earmarked for greatness. By the time he left, he appeared to be scoring for fun.

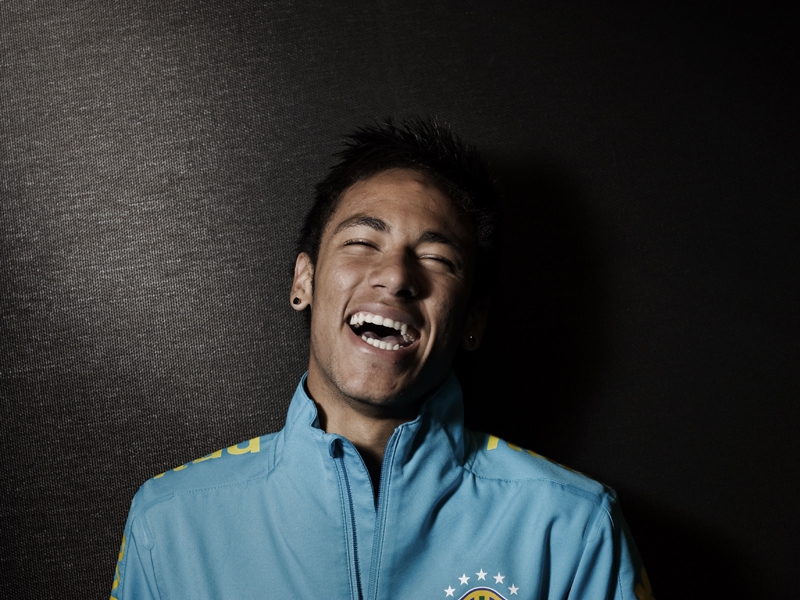

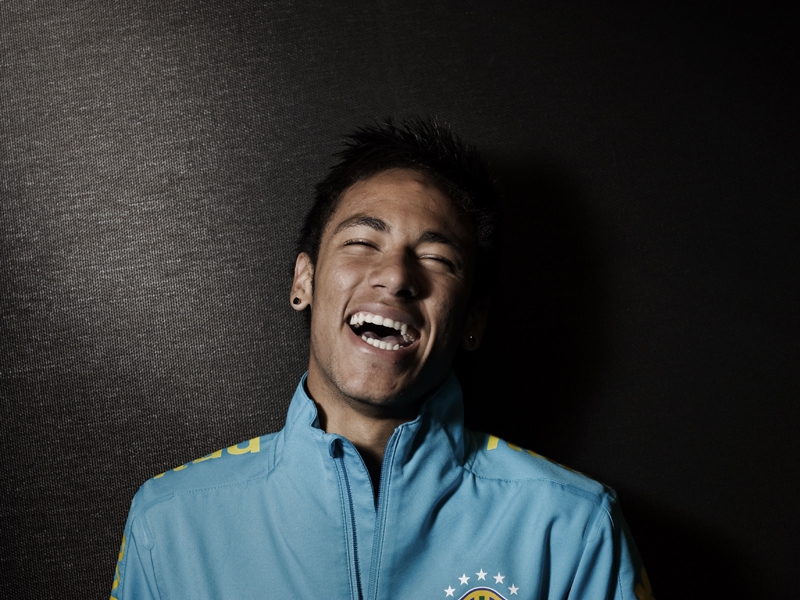

He walks in to the interview, a short, slight figure in an oversized Nike Air baseball cap, Nike T-shirt, track pants and a long necklace with a Number 10 – the number once worn by Brazilian demigods Pelé and Zico, and now in the national team by Neymar. He’s surprisingly thin, and there’s a bashful hesitance about his movements.

Among the tattoos on his arms are ones dedicated to various members of his family. His father, to whom he is very close, gets pride of place on his chest. One on his left arm says, “Life is a joke” in English, and next to a drawn fist is the legend, “It’s part of my history” in Portuguese.

Some sports stars give off a palpable aura, as if they’re able to claim a larger slice of personal space than average mortals. Neymar’s not like that. He looks awkward and shy, as though he’d much rather be playing video games at home. He portrays himself as a simple man, a guy with a penchant for dance music, who likes to eat rice and beans and biscuits and ice cream. Yet for the past two years, he’s been rated by SportsPro magazine as the most marketable athlete in the world. It’s been estimated that he makes £10 million from endorsements alone. I ask him about his vertebra, which he says – “Thanks to God” – is now fine. God comes in for quite a bit of name-checking. Religiosity is not uncommon among Brazilian players. Kaká, who was once thought of as Brazil’s leading hope, is a devout Christian, and several other players in recent years have cited God’s influence.

In addition, the heavenward finger-point has become an almost standard Brazilian celebration for goal scoring, and one that Neymar regularly practises himself. He was made captain of the national side in September, leading the team to a 1-0 victory against Colombia and scoring that single goal. We chat amiably through the interpreter for a few minutes. He says football is different in Spain from the game he played in Brazil.

“Here the defence is more professional, more dedicated to defending. In Brazil, they have to catch up in this way.” Does that make it tougher for an attacker? “The level of difficulty is higher for all the team, not just attackers. You have to be quicker in the way you think and respond.” What about the arrival of Luis Suárez, the Uruguay goal machine and serial biter, who was banned for four months from competitive football for sinking his teeth into Italy’s Giorgio Chiellini at the World Cup? Barcelona bought the toothy striker from Liverpool for a reported £75 million.

How could three of the world’s top four strikers (Real’s Ronaldo being the odd man out) play in the same team? There’s Messi, the quiet genius who’s said behind the scenes to exert an enormous influence on the Barcelona set-up and, some believe, team selection. And the mercurial Suárez. Where does the 22-year-old Neymar fit in with these two 27-year-olds in the prime of their careers?

“I’m flattered to play with both of them. During training, we chat about playing together and we try to make a strategy and some movements together. And I’m excited about all three of us playing together.”

We change tack for a while and, in true Life Beyond Sport style, discuss fashion. Do you like wearing sunglasses? I say. And do they help conceal your identity? He looks at the interpreter to check that she got the translation right. She repeats it and he sniggers. “I don’t know if they help in not being recognised, but I like to wear them because they suit me.”

In his autobiography, Neymar: My Story, he writes: “I like being authentic. I love working on my appearance, making bold choices for clothes, shoes, hats and earrings, but I think that’s just part of my generation.” Has he adapted his fashion sense in Barcelona? He looks down, toys with his cap, and mumbles: “Probably in Brazil, because it’s hotter, the style is more relaxed. I used to go to training in flip-flops and shorts. Here, it’s more formal. More dressing up.”

A nation of some 200 million, Brazil is to gifted football players what Saudi Arabia is to crude oil. They seem to come spurting out of the earth. Thus Neymar Sr, a journeyman professional footballer in Brazil’s lower leagues, would not have been the first Brazilian father to think his child had special football skills. According to the father, who shares alternate chapters in Neymar: My Story (subtitle: Conversations with my Father), he felt an intense affinity with his son from the moment of his birth. But it all could have ended long before “Juninho”, as his father called his first-born, took his first steps.

The family lived in straitened circumstances in the early years in Mogi das Cruzes, a favela of São Paulo. The parents, Neymar and his younger sister all shared one bedroom. But when Neymar was not much more than a toddler, a scout for Santos saw him running along a football stand and was struck by his natural balance.

It was the beginning of a relationship with Santos that would see the club pay for Neymar and his sister’s private education. Everyone realised that the boy was an exceptional talent. At 13, he was invited to Europe to play for Real Madrid, in the same way that Messi, at the same age, had gone to Barcelona. He went with his father, but returned home within three weeks. What happened?

“At first I was thrilled,” he tells me, “but after a few days, I started to miss my family and I was crying all the time. I wanted to go back to Santos.” The phrase the “new Pelé” has buried countless promising Brazilians, and it was used all the time about Neymar. This was partly because he played for Santos, Pelé’s old side, but also because there was massive expectation about this particular teenager. Like Pelé, he could read the game and was strong with both feet and his head. And he lived up to the hype, scoring in his first full match at just 17.

The following year, he was all set to move to Chelsea. But Santos fought a rearguard battle. They told him he could become the national hero the country had lacked since Ayrton Senna died. They put together a group of sponsors, in what became known as the Neymar Project, so that they could get close to matching Chelsea’s money. They auctioned off little parts of Neymar to advertisers, the way Senna’s car was a billboard for brands. And to clinch the deal, Pelé phoned the family and asked Neymar to stay.

Stay he did, but the word was that the attention went to his head. Critics said he began showing off, and then one day Neymar threw a massive strop on the pitch when Santos were awarded a penalty. His manager had selected another player to take penalties because Neymar had missed a few, but Neymar insisted that he wanted to take it. His team-mates remonstrated with him and he stormed around the pitch, then ran to the sidelines and abused his manager, a man called Dorival.“I know I was very wrong on that occasion. It was one of the worst days of my life. That was not me. I knew afterwards that I had to become a better man; I needed to mature.”

The club suspended him. But when Dorival insisted that the suspension should last not one but two games, the manager was sacked. Although Neymar had apologised to Dorival and played no part in the sacking, it was nonetheless viewed as an extreme example of player power. Several sponsors didn’t appreciate the bad-boy image. It was a turning point for Neymar.

To his credit, he kept his head down and applied himself. He won South American footballer of the year in 2011 and 2012 and was instrumental in bringing Santos their first Copa Libertadores (the South American equivalent of the Champions League) since 1963. He also established himself in the national side.

He matured in several ways, not least by becoming a father at just 19. His son, Davi Lucca, lives in Brazil with his mother (it was never a long-term relationship). But by 2013 it was time for Neymar to spread his wings. He had girls crying in the streets and boys copying his hairstyle – no mean feat when you consider he was sporting a cross between a punky spike and a mullet. He could barely leave his house. One time, Neymar played football on the beach with some friends, but such were the crowds that gathered that the police had to be called to enable him to leave.

All the great Brazilian players of recent decades – Ronaldo, Ronaldinho, Kaká – have tested themselves in Europe. Now it was Neymar’s turn, and in May last year he moved to Barcelona. His father said they chose the Catalan club over Real Madrid because it had greater “international projection”. The first year was not easy. Neymar went from being the centre of the team at Santos to one of Messi’s outriders. He scored 15 goals in 41 appearances. He says he found it hard to adjust at first because he missed his family and friends and his son. “Any change of country is difficult, because you’re out of your culture. But thanks to God and my friends and the club, I now feel more at home.”

For all his shyness, there’s something unflappable about Neymar. He doesn’t succumb to pressure. He says in his book that, to the amazement of his team- mates, he sleeps through bad turbulence on planes. And you sense there’s not much that would keep him awake at night, except, possibly, his dreams. When I ask him if he wants to be recognised as the best player in the world, as Messi has been for the past five or six years, he says that is not his goal. “I want to play well and play for my team. Just to be compared to my idol is an honour.” He may say that; he may even sometimes believe it. Rest assured, however, that the boy from Mogi das Cruzes has that number one spot in his sights.

TEXT: ANDREW ANTHONY // PHOTOGRAPHY: ALESSIO ROMENZI

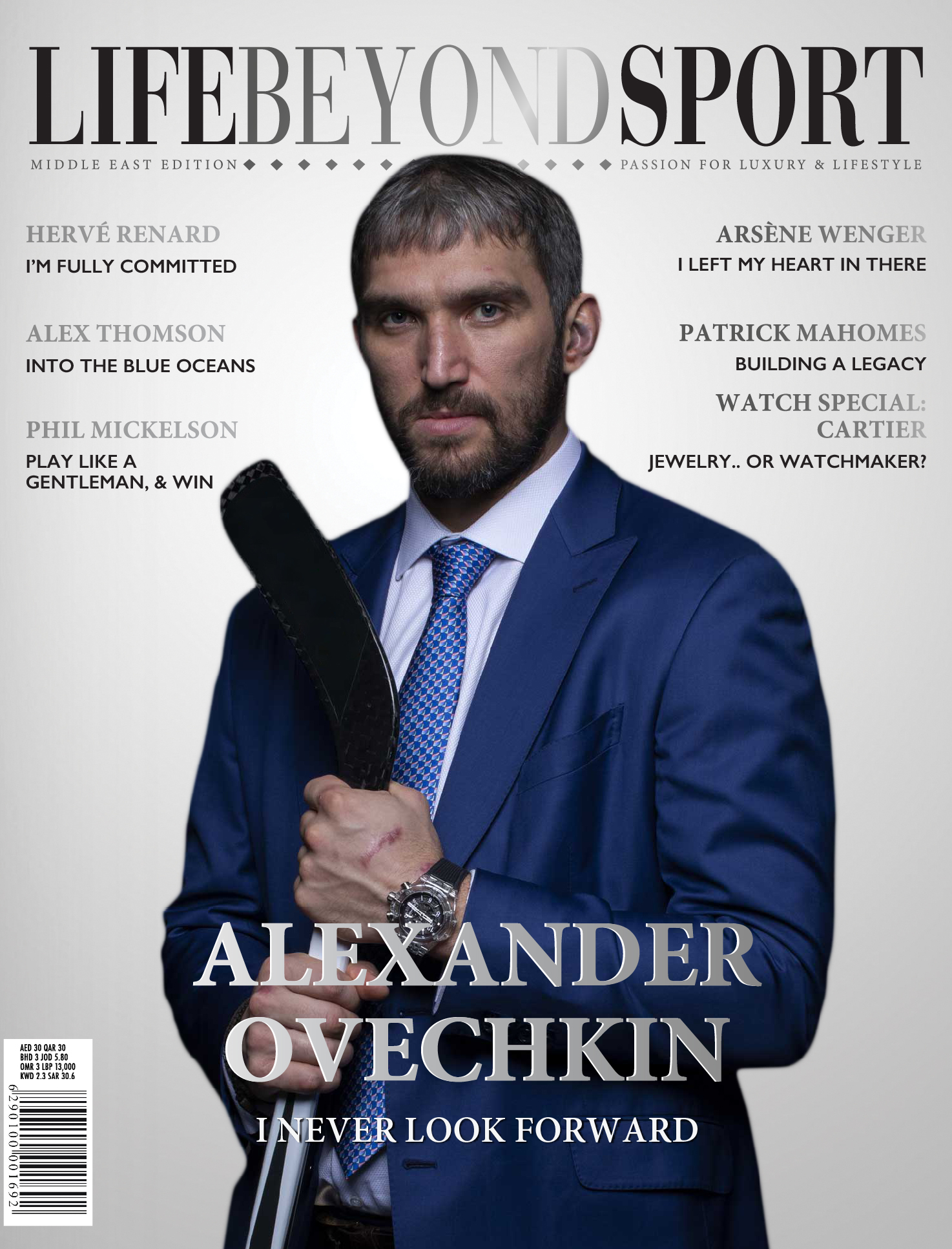

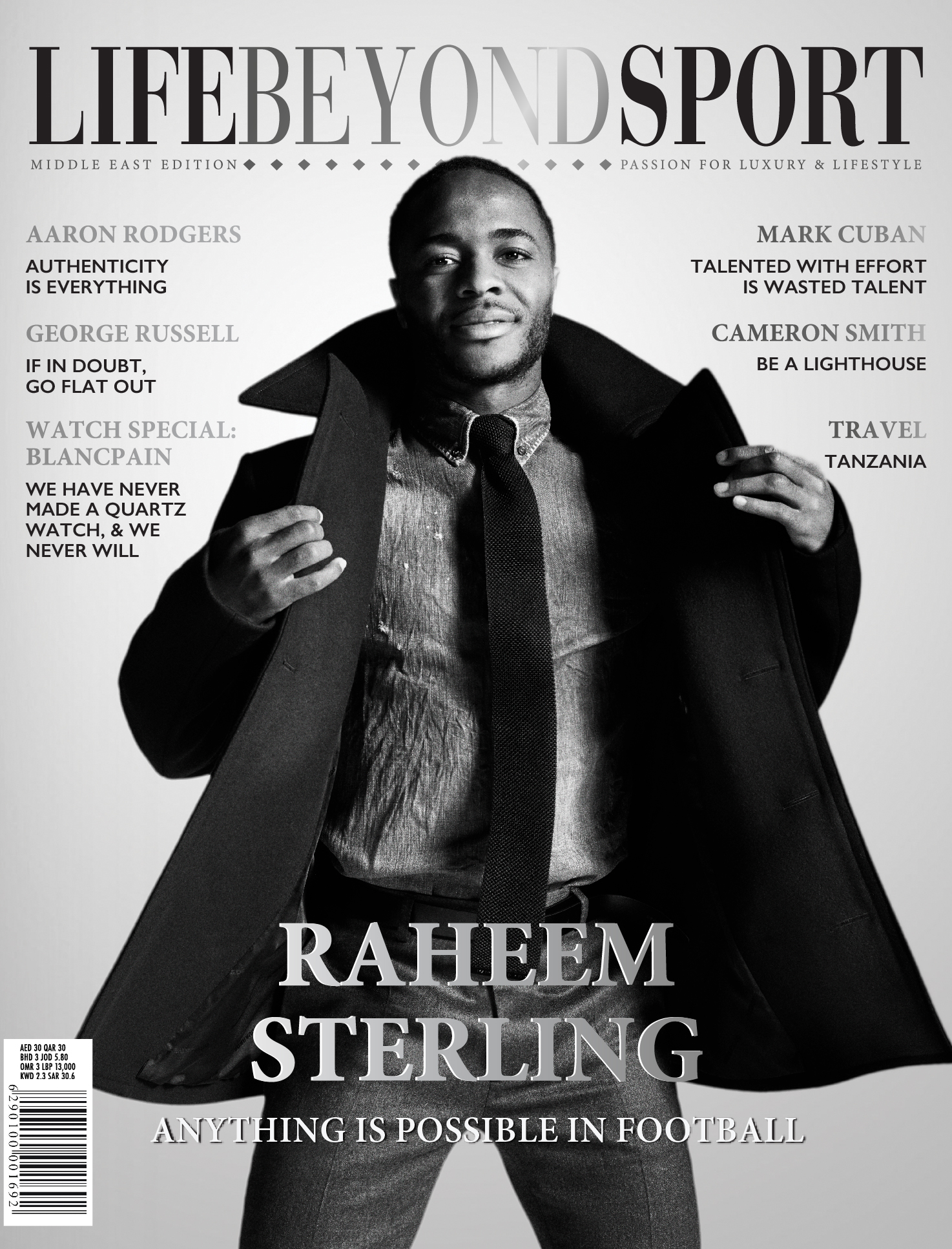

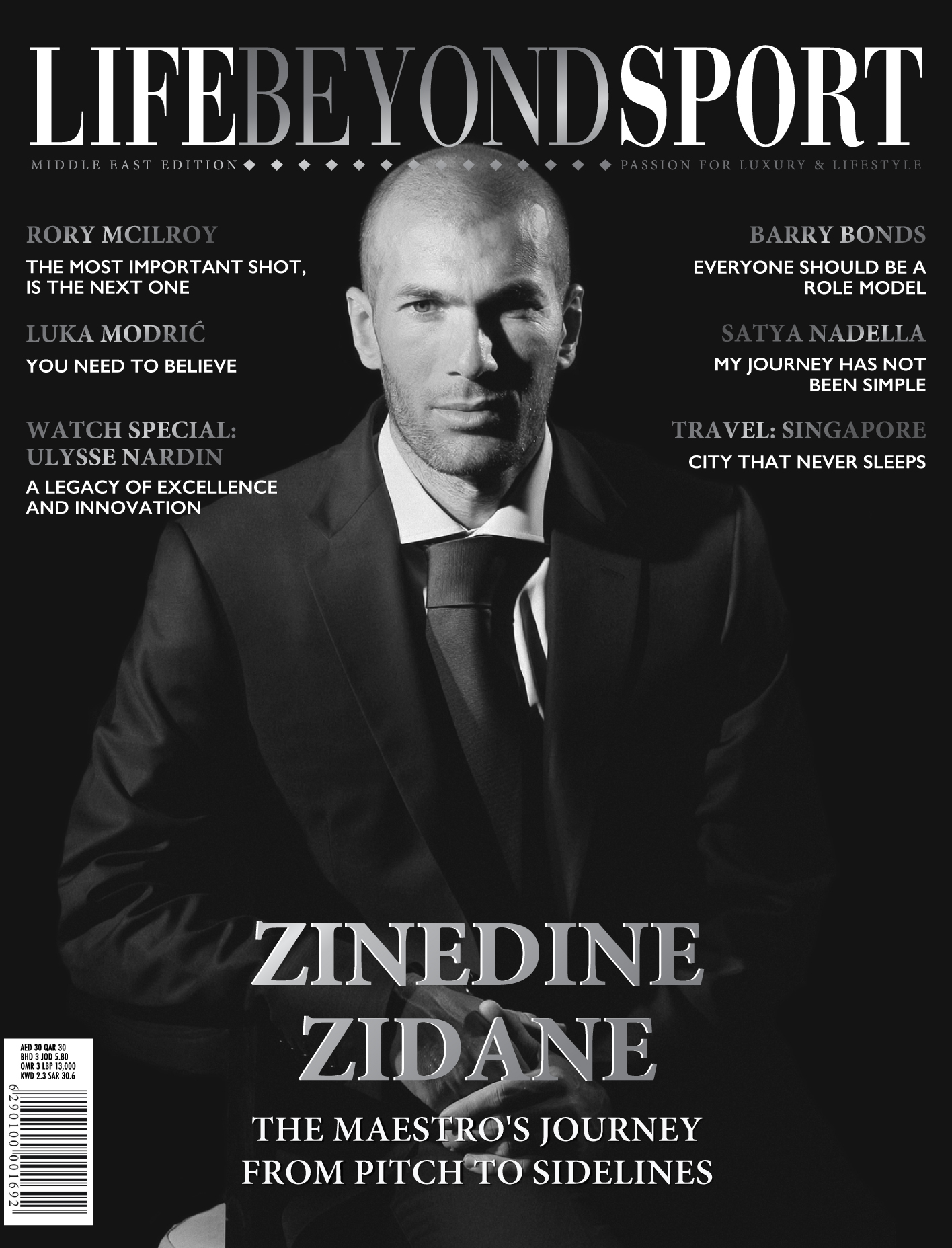

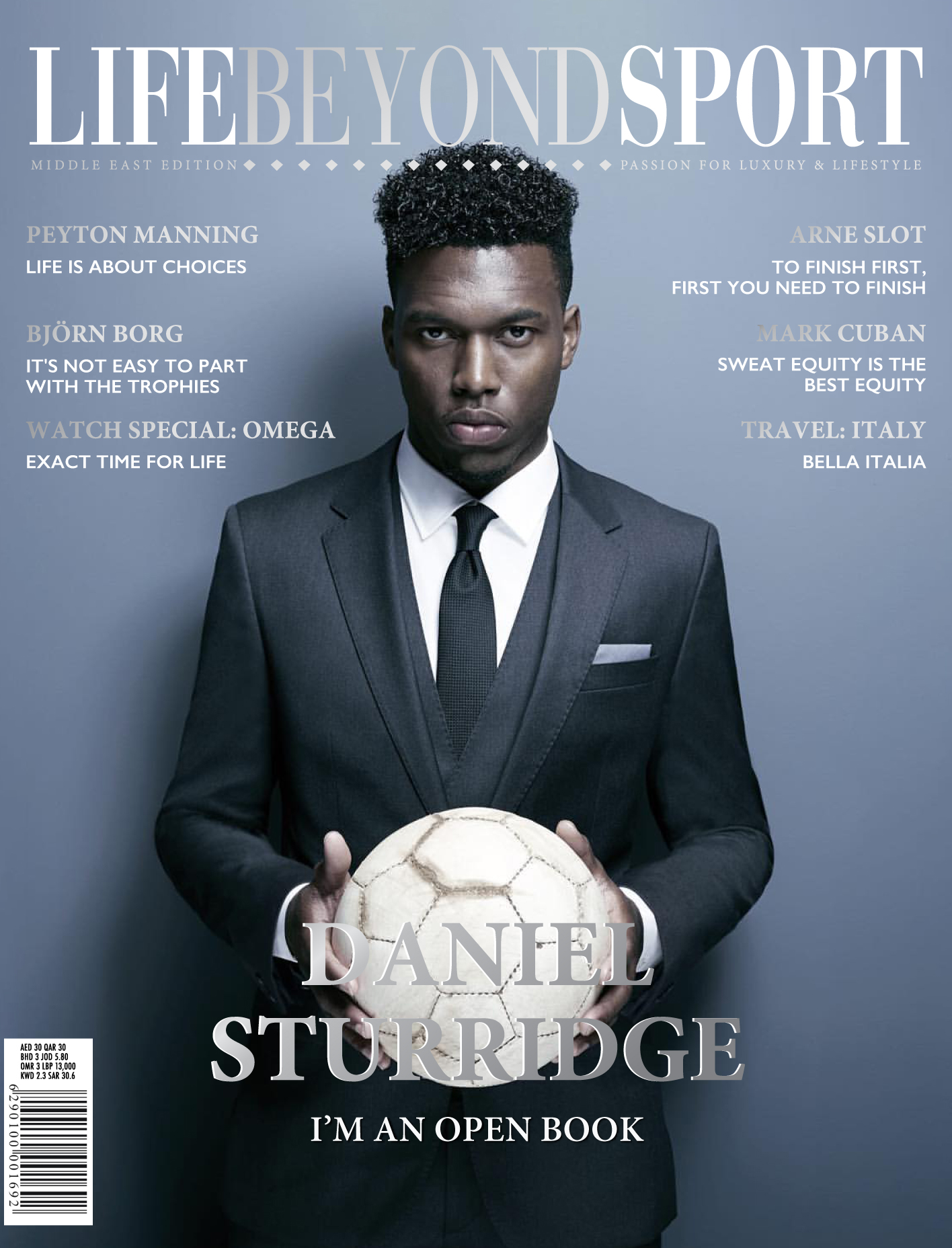

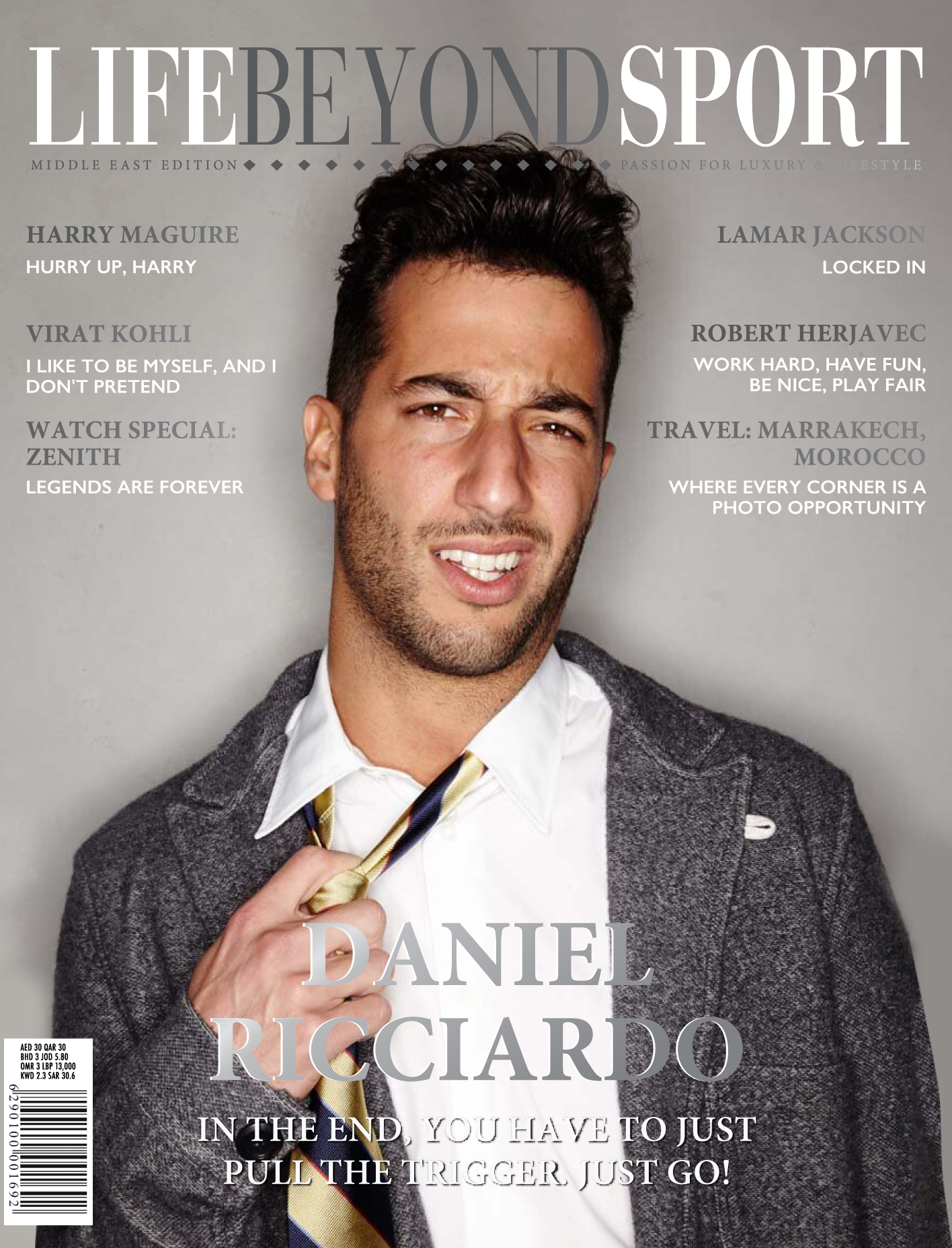

.jpg) Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.

Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.