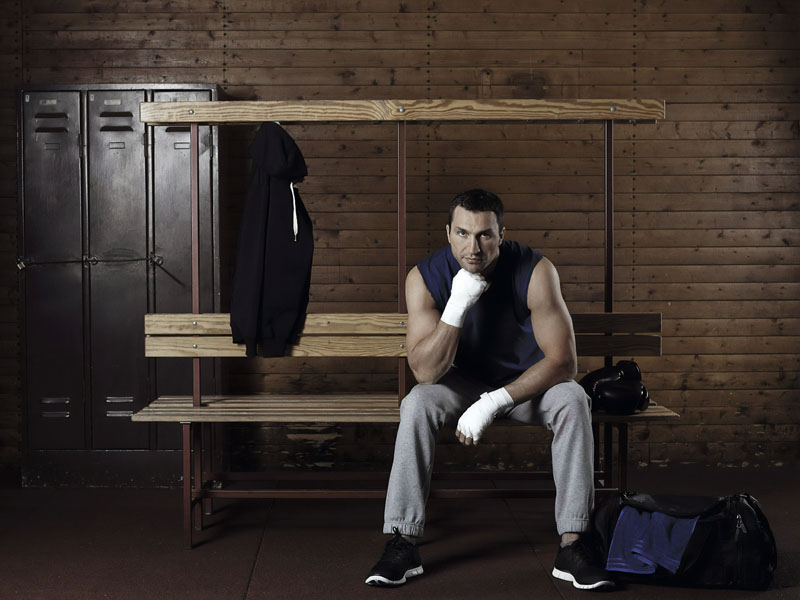

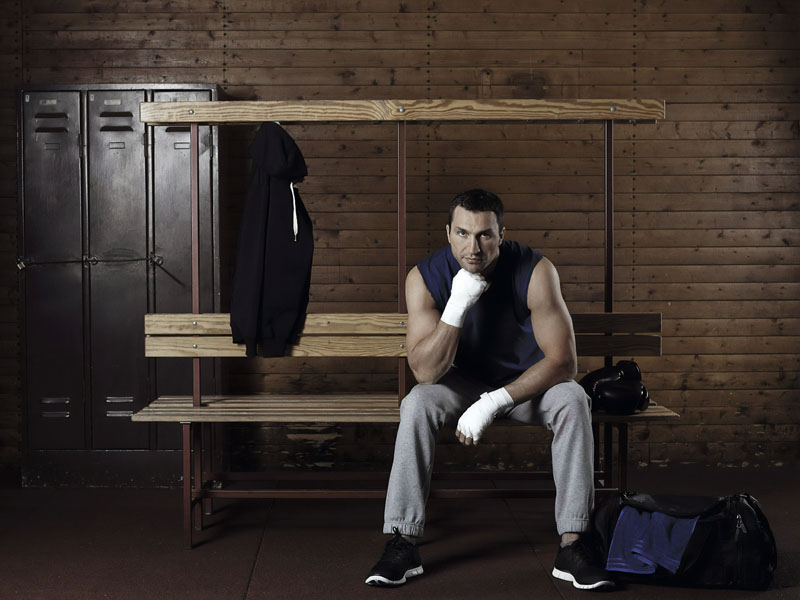

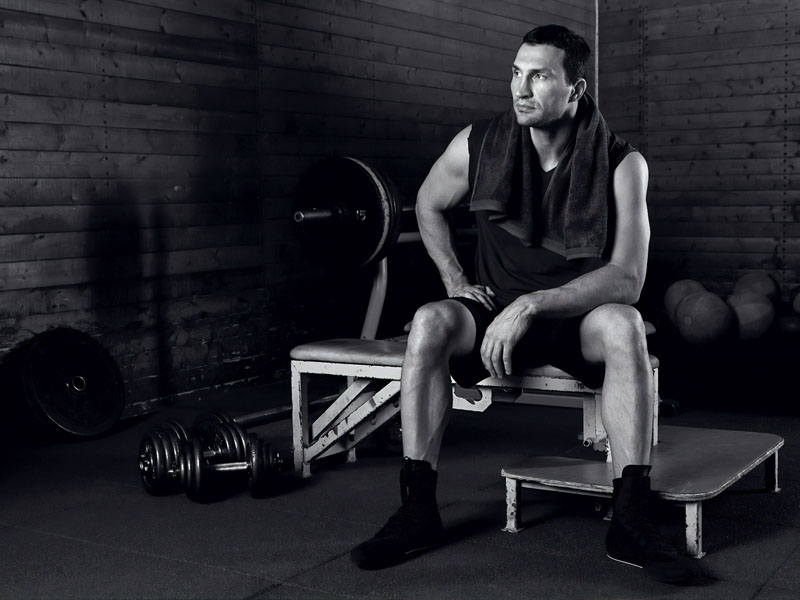

Wladimir Klitschko clasps my hand in greeting, his enormous right paw swallowing my tiny fingers. The former world heavyweight boxing champion is no stranger to sizing up the competition. He has agreed to play a game of chess but first he wants to know if I’ve got game.

TEXT: MURAD AHMED // PHOTOGRAPHY: RALPH PENNO

I tell him I haven’t played since my school days but admit to having taken a lesson the night before from a friend who plays at a local chess club. “Yes? Nice, me too,” replies Klitschko. He says he consulted a “mentor” to help him prepare. “Who’s that?” I ask. “Vladimir Kramnik,” he answers, referring to the Russian grandmaster who is not only a former world chess champion but a close friend of Klitschko’s. “I said: ‘Vlad, I’m going to play chess with the Financial Times.’ And he said: ‘OK, just stay calm,’ and he gave me a couple of hints. That’s it. I’m OK. I’m not anything special.” Already, I feel like many of those who have faced the 6ft 6in Ukrainian in the ring: way out of my depth. Klitschko, now 43, wore the heavyweight crown for more than a decade from 2006 to 2015, longer than any fighter other than the legendary American Joe Louis.

He says he was taught to play chess as a child by his older brother Vitali, who would also go on to be a world boxing champion. Together the siblings dominated the heavyweight division for around a decade, though they promised their mother they would never fight each other. Boxing and chess were rare constants in the brothers’ peripatetic upbringing. “He was my best friend,” says Klitschko of his older brother. “We [were] travelling so much. He was born in Kyrgyzstan. I was born in Kazakhstan. Then, we went to the Czech Republic [and] to Ukraine . . . All this time, when you’re moving from one place to the other, you cannot have longer friendships with the kids or classmates in a school. I changed like seven schools during my school [years], and my best buddy was my brother. So, we had to entertain each other in certain ways. Chess was one of the things that we experimented with.”

Again, he seeks to reassure me that, on the board at least, we will engage in a fair fight. Again, he fails. “I did lose against Garry Kasparov once,” explains Klitschko. I protest that now he is merely name-dropping another former world chess champion. “As my friend says, do something good and talk about it,” he says with a meaty chuckle. “I’m proud to have shared the same room and same board with Kasparov.” Klitschko says he lasted 25 moves before losing to one of the greatest chess players in history. A strong effort, I suggest. “I’ll be honest with you, if Kasparov wanted, he would have done it earlier. He was just like: ‘OK, I’m going to let you enjoy it. I’m not going to knock you out in the first round.’”

We have come to Alfred’s, a private club in London’s Mayfair, where Klitschko is a member. The interior is steeped in the eccentricities of the English gentry. Glass cabinets filled with smoking pipes are set alongside paintings of bulldogs. It seems an incongruous setting for a man who is a working-class hero in Ukraine, the country he eventually settled in as a teenager, and in Germany, where he was based for the vast majority of his career. But Klitschko says he forged an unbreakable bond with London following his epic fight against British boxer Anthony Joshua 2 years back.

Before the bout, Klitschko and Joshua spoke of their mutual respect for one another, a refreshing antidote to the trash-talking that routinely accompanies modern title fights. The contest took place in front of 90,000 spectators at Wembley Stadium. Klitschko fought bravely against an opponent 14 years younger than him and came close to victory but was eventually stopped in the 11th round.

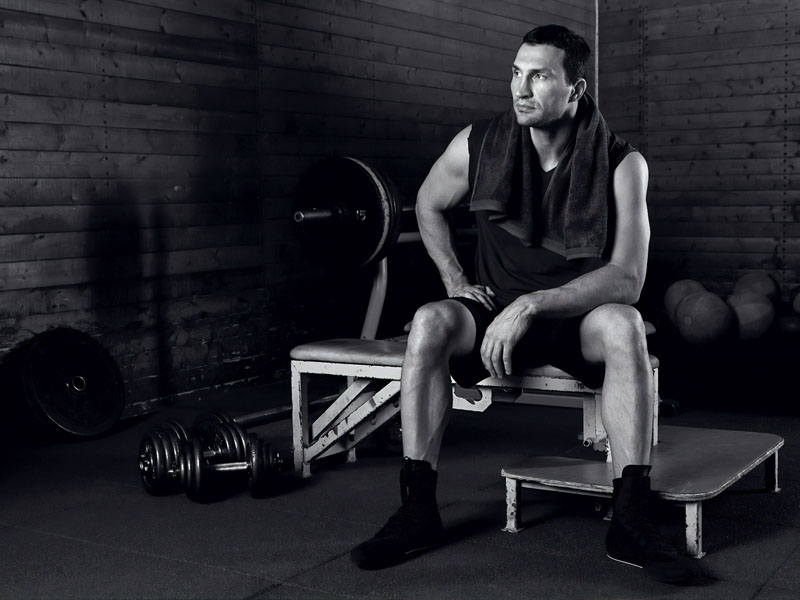

He could have made millions by forcing a rematch but instead chose to retire. “I was cheered out by the audience, by the fans of Joshua,” he says. “I had lost, but my stock went up. The next step, when I was thinking yes or no for a rematch, I said no. My stock went up again.” He revels in the irony that, though he has the record of an all-time great, it took a defeat for him to fully gain the respect of the boxing public. For much of his career, Klitschko was not widely loved. Despite towering over most boxers, his style was cautious, meticulous, often unspectacular. He failed to connect with fans in boxing’s lucrative American market. Does he feel under-appreciated? “I’ve been asked many times during my sporting career: ‘What do you think about your legacy?’” he says. “I didn’t care about my legacy. I just want to be myself. Will it be received well or not? I cannot really control it.” Now at the end of his boxing career, can he look back at his achievements with pride? Klitschko rejects the notion. “If I’m going to be proud, I’ll stand still. Standing still means not moving forward. Standing still means falling back. If I think I’ve made it, I’m done. If I think I’m proud, I’m done. I’m not proud. I’m satisfied with my first career.”

Klitschko is fond of esoteric statements like this and projects the air of a deep thinker — hence our game of chess. Not that he has much to prove. He speaks four languages and has a PhD in sports science from the University of Kiev. The topic of his dissertation was “Pedagogic control over young athletes, ages 14 to 19, in the old Soviet Union”. The doctorate explains his nickname: Dr Steelhammer. Klitschko has always been proactive about his career outside the ring. While he was still boxing, he began sidelines as an entrepreneur, investor, hotelier and philanthropist. For his next act, though, he wants to be considered something of a philosopher too. He has co-written a book, Challenge Management: What Managers Can Learn from a Top Athlete, featuring testimonials from Bill McDermott, chief executive of corporate tech giant SAP, and Arnold Schwarzenegger, the action-movie star who became governor of California.

Klitschko believes his experiences provide life lessons that can be transferred to politics and business. The idea of sporting champions as management gurus is well established. Football managers such as Sir Alex Ferguson and Carlo Ancelotti have released leadership manuals designed to be consumed by C-suite executives. But Klitschko has taken things a step further. In 2016, he founded a programme at the University of St Gallen in Switzerland, where students can take courses based on his theories. In his book, he says that before any fight, he visualised the fighting style of his opponents while also imagining victory. He believes the same approach can work in any negotiation. “Internalise your winning pose,” writes Klitschko. “Save similar motivational pictures on your smartphone and have a look at them if you have doubts.”

Why not put such theories into practice? His brother Vitali is the mayor of Kiev, having been a key figure in the Maidan protests that opposed the rule of former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych. A war still rages between pro-government forces and Russian-backed rebels in the east of the country. Will Wladimir follow his brother into elected office? Klitschko says politics in Ukraine is no game. “One politician in the family is good enough . . . [Vitali] is a true fighter. He was born this way. I learnt how to become a fighter. The fight that he has today is longer than any other fight in his sporting career, and it’s the most complicated. Politics has no rules. In the boxing ring, you can get a bloody nose or a black eye. In politics, you can get a bullet in the head or dioxin in your food.” With that, we move to the chess board.

After a few moves, I become more confident that Klitschko really is not a grandmaster-in-waiting. For instance, neither of us notices until well into the match that the pieces have been laid out incorrectly. Our king and queen were set out on the wrong squares. This does not change the fundamental dynamics of the game, but gives some indication of the quality of our play.

According to my opponent, there are some unlikely parallels between top-level boxers and chess players. His friend Kramnik told him that grandmasters “lose an incredible amount of weight during a tournament”. “Some tournaments,” Klitschko says, “are long. It shows how much energy and calories your brain can burn. They lose like, if I’m not wrong, during the two weeks or week and a half, up to 20kg. If they go to sleep, they cannot really turn off their mind. It’s just constantly doing combinations and combinations and combinations.” Initially, he humours me by putting up with continued questions during play. Did he ever talk to his opponents in the ring? “Like [Muhammad] Ali?” he asks. “No.” “I’ve been bitten,” he adds. “Then I was a little bit talkative.” He is joking, but I take it as a prompt to be silent. As we focus, Klitschko hums and taps his feet. I make a few attacks into his territory, but he parries these. I suggest to Klitschko that his approach is cagey, not unlike his boxing style. He asks if this is a compliment. I insist it is.

“The first mistake is going to be the last,” he says. Klitschko is used to a sport where dropping your guard results in a punch in the mouth. “In boxing you’re going to feel it right away,” he says. “It’s not going to take a long time.” We have allocated 45 minutes for our game but time is running out. I hint that perhaps we should abandon the board in an honourable draw, but this does not seem to suit Klitschko’s competitive instincts. Instead, we switch into a game of “blitz” chess, where moves have to be made within seconds.

Speeding up the game results in him making the first major error. He loses his queen, the most powerful piece. Suddenly, I’m in a winning position. I move my own queen into the open, seeking to push for victory. But it is a boneheaded move, placing it in the path of one his pawns. I realise the mistake instantly. A split second later, Klitschko takes my queen. It is a sucker punch. Left with just a few pawns, I’m in a hopeless position. I resign. Klitschko wins. The champ appears genuinely elated and takes a photograph of the final board to send to Kramnik. “It’s an exciting game because it’s a war with an army,” he says of chess. “It’s a lot of co-ordination, a lot of focus, a lot of endurance. You have to be really agile in everything you do. It actually fits well into sporting life, into business life, into private life, into anything. It just matches with my genes.”

TEXT: MURAD AHMED // PHOTOGRAPHY: RALPH PENNO

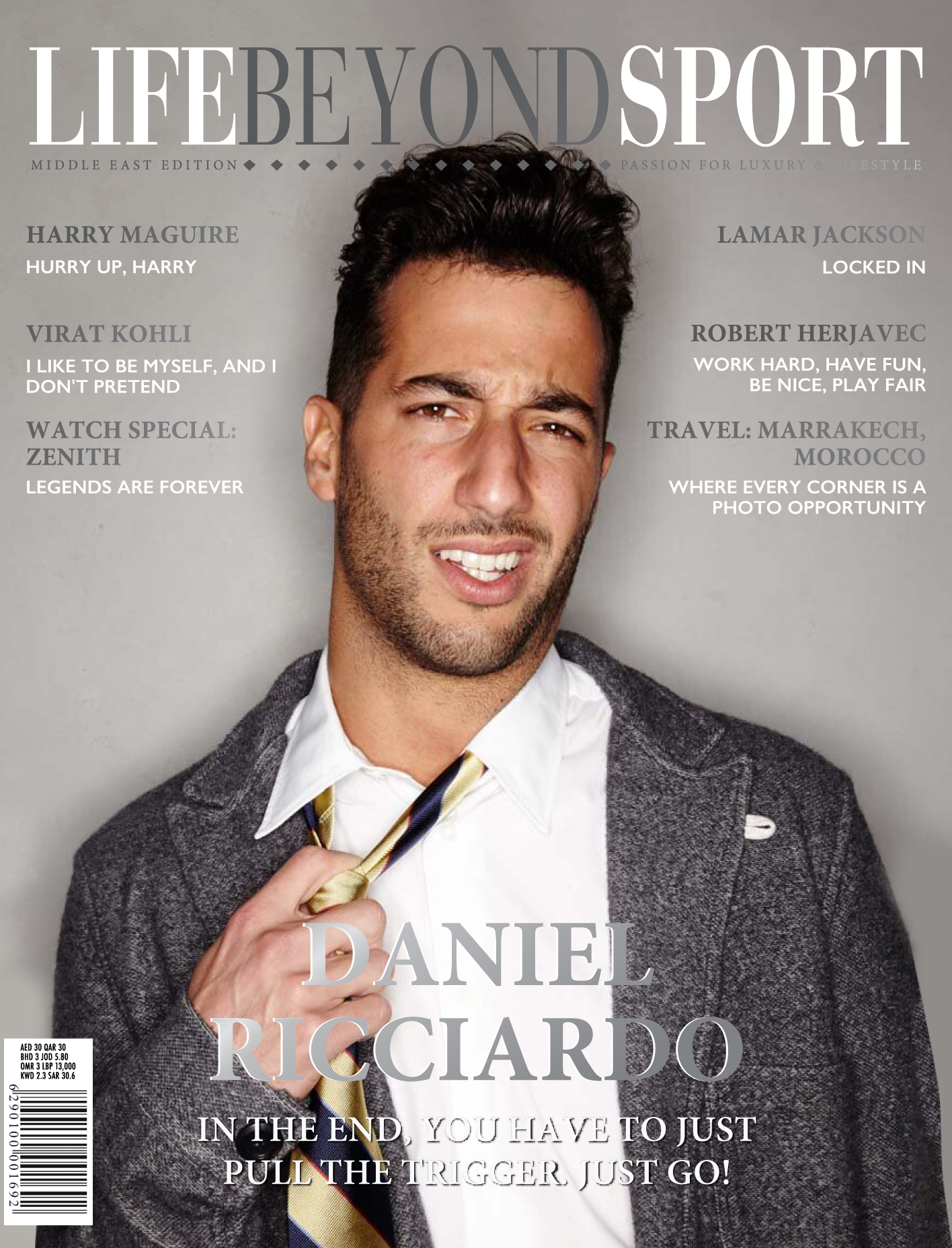

.jpg) Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.

Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.