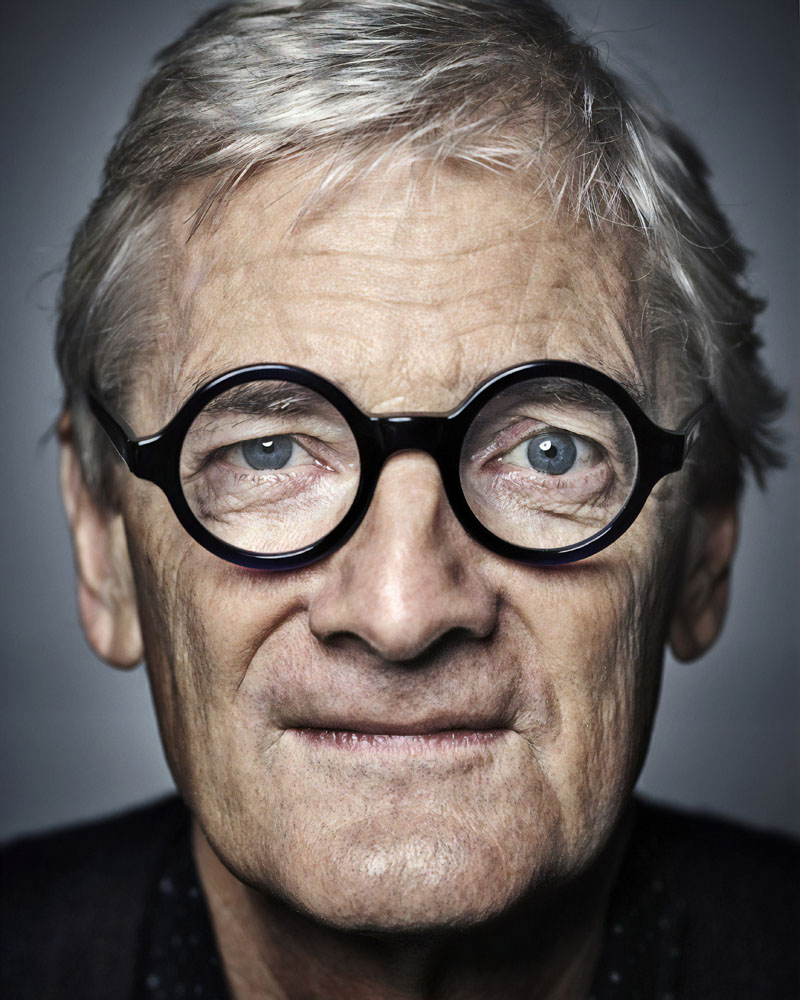

He made billions selling vacuums. Now he is backing Brexit, building an electric car — and making antiquated comments on ‘racial differences.’

James Dyson is unapologetically British.

The product of the English boarding school system, Mr. Dyson found his calling as an industrial designer and built one of the most successful private companies in the United Kingdom by selling his distinctive vacuums. He was knighted in 2007, served as the provost of the Royal College of Art in London and is one of the country’s richest men.

Yet in a globalised economy, Mr. Dyson remains intently focused on what he believes is Britain’s exceptional place in the world. He wistfully refers to the British Empire, and unlike most in the business community, is in favor of Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union, believing Brexit will make the country stronger economically and culturally.

In this interview, Mr. Dyson expressed antiquated and at times offensive views on “racial differences” and Japanese culture. He also referred to growth markets in Asia as the “Far East.” When asked to clarify his remarks, Mr. Dyson declined to comment further. (Read a portion of his comments on Japan below.)

Mr. Dyson discovered his passion for design at an early age, and eventually began work on his signature product, the bagless vacuum cleaner. It took several years, but he brought the product to market, founding Dyson Ltd. in 1991. Soon, Dyson was expanding internationally and developing new products, including washing machines, fans, heaters, air purifiers, hand dryers and hair dryers. It is now at work on an electric car.

However Brexit plays out, Mr. Dyson’s company looks like it will endure. It posted a strong jump in sales last year, thanks in large part to strong sales in Asia.

This interview, which was condensed and edited for clarity, was conducted in New York.

What was your childhood like?

My father died when I was quite young. He was a teacher at a boarding school, but he didn’t have life insurance, so the school allowed my brother and I to continue there. Boarding is pretty harsh stuff. You’re sent away for 14 weeks, and your parents could visit you one Saturday a term, and that was it.

“Feelings” is a word I didn’t know until I was about 50.

How did you get interested in design?

I did art at boarding school, which I really enjoyed. So I decided to go to art school in London. That’s where I discovered design and thought, “That’s what I want to be doing. I want to be designing and creating things.” I started off with architecture, and then I discovered Buckminster Fuller, the great American inventor, entrepreneur. And suddenly, the thing that was interesting me the most was the thing I always thought was incredibly boring, which is engineering.

What was your first job?

What was your first job?

When I was in college, I went to this industrialist at an engineering company. He said, “I’ll give you some design jobs.” He had this idea for this high-speed landing craft for the military and said, “Why don’t you design that?” I knew nothing about boats, though I didn’t dare say it, but it sounded fun. So we built a prototype, and then the chairman of the company said, “Well you better start selling it.”

I looked at him slightly blankly and said, “Well, don’t I have to do some market research?” And he said, “Don’t bother. It’s a good product. Anyway, you’re the engineer, you know every nut and bolt of the thing.”

And you sold them?

I didn’t look like a business man or anything. I had flowing trousers, long hair, flowered shirts. But I set up the company and manufacturing, and I sold them for five years. We sold them to militaries all over the world, to oil companies, construction companies, smugglers bringing American cigarettes into Italy.

Smugglers?

He came in a leather jacket and paid cash. I asked him what he was going to do, and I didn’t think smuggling cigarettes was particularly naughty.

The point is, here’s this longhaired art student in the mid-’60s, getting asked to design something he knew nothing about. Then he’s told to set up a company, which he knew nothing about. That’s what I do today with my people. I try to recruit everybody as a graduate, because they have no baggage, they have enthusiasm and curiosity. I think experience can be fine in certain situations and with certain companies. But when you’re doing something very different, it’s often best done by people who have done nothing before.

“The public wants to buy strange things, as long as there’s purpose to them.”

How did you come up with the idea for the vacuum?

I decided to pick a modest product and do a completely different version and see what happened. But the retailers weren’t interested, because they said it was too different and they said they didn’t have space for a different thing made by a nobody. So I decided to advertise in newspapers. And what I learned is that the public wants to buy strange things, as long as there’s purpose to them. As long as they can see what’s new and different about it, they’ll buy them.

And what was so different about your vacuums?

I saw the problem, and I saw a possible solution, which was the huge cyclones outside cement plants and timber yards that collect dust all day long. So I started building various versions of that technology. As it happens, it didn’t work. I had to spend four or five years coming up with different types of cyclonic separation devices in order to make it work.

It took a lot of empirical work. I had to build the prototypes, one or two a day, which sounds tedious, but actually it was fascinating. I’m still doing it today. It always is a wonderful adventure of excitement and disappointment. Almost everything you do is a failure, until you get the one success that works.

How did you pay for all that research and development before you had a product to sell?

How did you pay for all that research and development before you had a product to sell?

I was borrowing it all from the bank. Going deeper and deeper into debt. By the time I launched the vacuum cleaner, I was two million pounds in debt. I think the bank got in a bit deeper than they intended to, but I had an interesting bank manager. I asked him why he lent me the money, and he said, “I went home to my wife and said, ‘What do you think about vacuum bags and vacuum cleaners?’ And she said, ‘Dreadful, dreadful.’”

Once you gained traction in the U.K., how did you expand into the United States?

A junior buyer at Best Buy took our vacuum cleaner home and used it for three weeks and came back to her boss and said, “This actually is a really good vacuum. It doesn’t make a mess.” And he said, “All right, let’s give it a go in 50 shops.” It sold well, and then everybody else wanted it. It was just one brave junior buyer, convincing her manager.

When we met before, you told me something about Japan.

We do a lot of our product launches in Tokyo. They’re technology nuts. They love artifacts. In this P.C. world, we like to not say anything interesting about people that are different from us. But the Japanese were, when I went there, very, very different. They told me I have a nose like the Eiffel Tower. The girls want to spend their whole teenage years to get their noses more like Western noses. I think racial differences are fun. And they’re sometimes funny and they’re a source of amusement between us. But of course, that’s not a very P.C. thing to say.

Whenever we went there, we thought you had to learn to behave like a Japanese person, you know, bowing. What I quickly learned is that’s not what they wanted from us at all. They wanted our eccentricity and difference. So, I carried on being an Englishman.

What are you working on now?

I’ve been working on an electric car. We bought an old World War II airfield, so we’ve got a place to do it. Tesla proved that people want electric cars, though I don’t think governments have realized it yet. People are trying to ignore pollution and the damage that pollution does. Apart from that, the electric car is a much nicer and easier car to own. You don’t have to go to gas stations, which aren’t very nice.

How do you identify what markets to go after?

I don’t really look at markets at all. Otherwise, I would have never gone into hand drying. When we have technology we feel could do something interesting, we go into that field. It’s entirely technology- and product-led. It’s not led by market size. Hand dryers are not a sexy business, but we had the technology which did it better, and it happens to be a perfectly reasonable business. It’s not like computers or mobile phones, but we wanted to do it and we enjoyed it. We still enjoy it. I choose unpopular fields to go into, because they’re more interesting. I want to play the bassoon, please. Playing the guitar is much more sexy, but the bassoon is more interesting.

Why are you in favor of Brexit?

I think we should be independent. Europe has become more and more of a unified society where all the laws are made in Brussels. I don’t believe it’s ever been right for Britain.

Britain has always been a globally facing country, with our empire, if I dare mention that, covering half the globe. We have a pioneering and global outlook. There’s no room for us in Europe.

What about the prospect of economic disruption to England

All cars coming into England from America have a 10 percent duty on them, and most of that goes to Brussels. Europe is a protectionist setup designed to keep competitors out. It’s not a good thing to be in. We believe in free trade. And if any bankers are leaving London, it’s got nothing to do with Brexit. It was the right decision for Britain.

TEXT: DAVID GELLES // PHOTOGRAPHY: HEATHCLIFF O’MALLEY

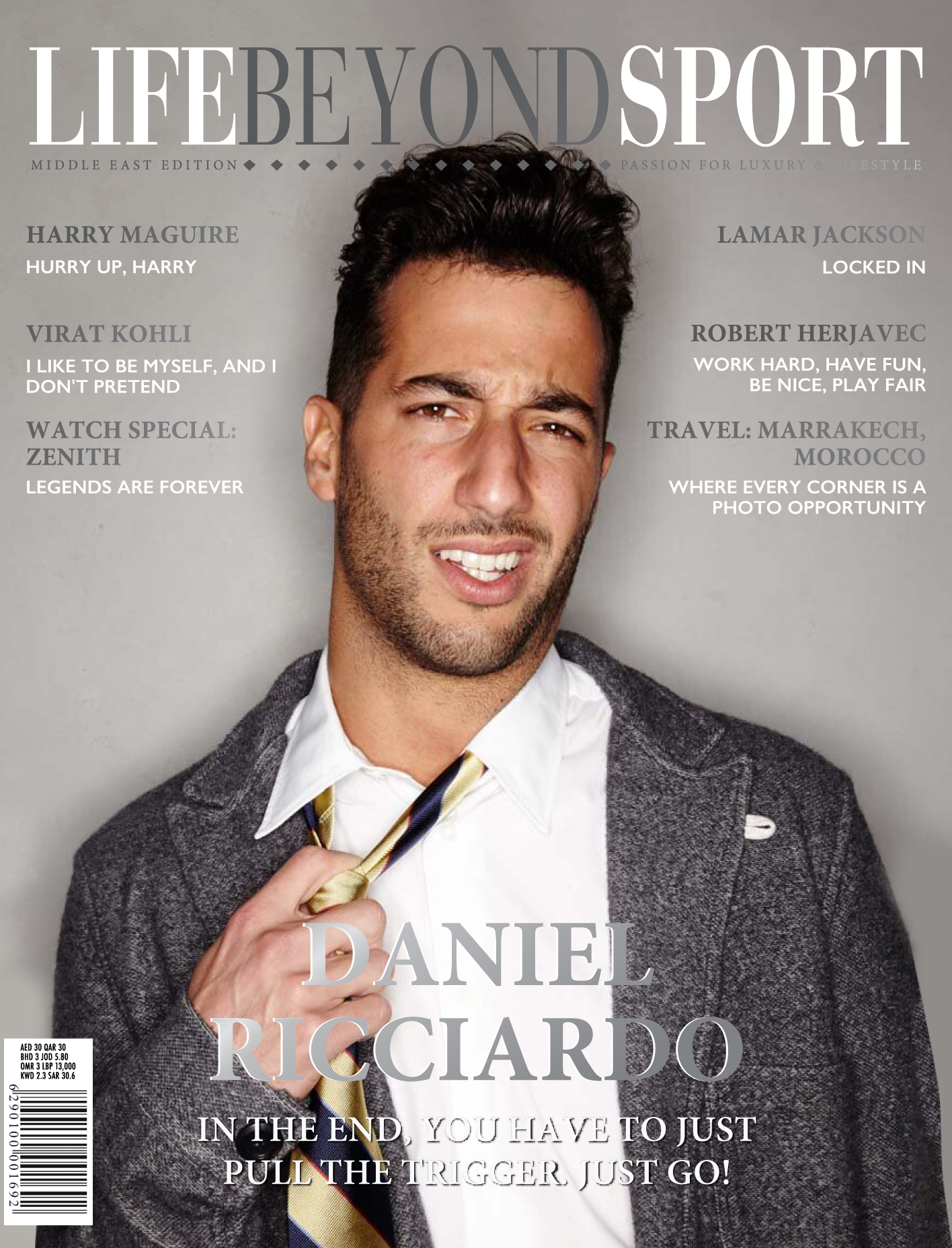

.jpg) Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.

Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.