In his two seasons with the Utah Jazz, he has delivered some incredible moments on the court but he has also popped up in the community at neighborhood cookouts, helping people with phone repairs, or aiding crash victims, at basketball games and other places newly minted pro sports athletes aren't typically found.

He has credited his mother often in the media, but in our interview, Donovan Mitchell and his mother Nicole Mitchell, tell the story of young Don Mitchell and his surprise rise from school boy to a NBA star.

I already know the first question you’re going to ask.

“Donovan, why is your mom the guest editor for this story?”

I’m asking myself the same thing right now.

Of all the people in the world with incriminating evidence on me, my mom probably tops the list. She’s got all the embarrassing stories. The thing is: She doesn’t trust me, you guys. My mother does not trust me with my homework assignments. This goes way back.

Guest editor Nicole Mitchell: This goes way back.

The only way I can possibly do our story justice is with her by my side. This is the way it’s always been. See, when I was a kid I guess I was a little bit extra.

Editor’s note: Donovan was very extra. He had a lot of energy. He was … let’s call it exuberant.

I was running around everywhere. But like, to no fixed destination. For no real purpose. Just running, man. There’s no photographic evidence of this, thank God, and I don’t even know if this is legal anymore, but when I was three or four years old, I swear to you that my mother used to put me on one of those kiddie leashes whenever we’d go anywhere.

‘’I swear to you that my mother used to put me on one of those kiddie leashes whenever we’d go anywhere.’’

A harness. O.K. a harness. Anyway, we would be going to Marshalls department store, and I know that anybody reading this whoever had to go to Marshalls as a kid knows what I’m talking about. That toy section was nonexistent, man. There was nothing fun in there. Your mom would be comparing 12-packs of socks or whatever, and those aisles were so long and shiny. What were you gonna do? Take off. Run wild.

So after losing me a couple of times in Marshalls, she put me on the leash.

Editor’s note: Harness! It was for safety purposes. I had to keep him in check! If he saw a nice open space, he was gone. Don got calmer with age, and he graduated to the little wrist leash. I’m sure the world loved me for it.

I was so young that I barely remember it, but I think that really says it all, right? Even now, when I’m on the bench in Utah, I can barely sit still. I think I was just born like this.

Editor’s note: Donovan will deny this, but I came to pick him up from day care one day, and the lady said, “You know, Donovan is always jumping up on the tables and dancing. He just hops right up there and all the kids watch him.” And I guess I should’ve been embarrassed, but I thought it was so funny. Because whenever we used to go over to his grandma’s house for dinner, we’d clear off the coffee table and he’d hop up there and dance to her old records. That was our ritual. We’d have a nice little dance party. And I know Don is going to be so embarrassed that I’m saying this, but you know who we loved to listen to? Kenny Rogers. Imagine that. This little boy dancing on a coffee table to Kenny Rogers.

No evidence. Lies.

The real story is that I was obsessed with sports. Basketball and baseball were the main ones. When my friends weren’t around, I used to play imaginary five-on-five in my head. We had this archway between our living room and dining room, and I’d jump up and slap it. That was my hoop. That’s how I dunked. Everything was in my head — the pick-and-rolls, the inbounds passes, the crowd. I’d be talking imaginary trash and everything.

Editor’s note: Oh my gosh, I used to hear him slapping the arch all day. When I’d be cleaning the house, I was too short to reach up there with the rag. So when we moved out, the handprints were still up there.

The thing is, my mom was skeptical about sports. Incredibly skeptical. She was all about education. We were living in White Plains, New York, at the time, and I didn’t really understand the struggle that she was going through. But she had a vision for me and my little sister, Jordan. When I was in third grade, I got the chance to go to Greenwich Country Day in Connecticut, which is one of the best private schools in the country. I mean, at the time I had no idea what any of it meant. I just knew that I had to leave all my friends, and I was heated.

I’ll never forget going to stay with my host family on the first weekend in Greenwich, and I couldn’t get over how big the houses were. It was kind of mind-blowing, honestly. I remember saying to the family, “You actually live here?”

It was a little bit of a culture shock. I was one of the only black kids at the whole school, and it was the first time I realized that there’s money and then there’s money. Remember that first time you realized how different people’s lives can be? Greenwich was a 30-minute drive from our house, but it was a totally different world.

Maybe some people reading right now can relate to this feeling — like the first time you go out to get something to eat with your new friends, and you have to do the whole, “I’m not hungry, I’m good,” thing. But then when you do it the third or fourth time, and you’re the only one not eating, everybody kind of knows the deal. When you’re young, that can be a really harsh reality.

I didn’t understand how much my mom was sacrificing for us. I’ll never forget the time I came back out to the car one day to grab something that I forgot, and I saw her sitting there in tears, all by herself. She never wanted us to see her stressed. I guess when things got overwhelming, she’d go out to the car to cry … just to get it all out. Then she’d come back inside like nothing was wrong.

We had no idea, but at the time she was always worried about how she was going to pay the rent that month, how she was going to buy us clothes, how she was going to pay for gas. She shielded us from all that. Her whole vision was to do whatever it took just to get us to graduate from Country Day. Because that’s something they could never take away from us. And, man, I have to admit, I made it hard for her sometimes.

Any kids reading this who are dreaming about playing college ball: You think those freshman and sophomore grades don’t matter? They matter. I almost messed up my whole future because I didn’t take those years seriously. I was so bad. I used to go to the nurse and tell her that I had a migraine, and then I’d go back to my dorm room and take a nap before practice.

Don’t do this. I was being reckless.

My mom could sense it. I don’t know what kind of next-level ESP she has, but she called me up one day out of the blue, and she told me, “You’re acting out of character. You’re not that same humble kid you used to be.”

Honestly, I just blew her off. I’m 15 years old. I know everything, right?

But I’ll never forget her exact words before she hung up. She said, “Let me tell you something, sweetheart. God is going to make you recognize that you have to be that same kid you’ve always been.”

A week later, I broke my wrist.

I missed an entire summer of AAU, and that’s right when everybody is getting ranked and hyped up and getting offers from colleges. I was beyond devastated. But I got the message. I was trying to take shortcuts through life. Just sitting around, watching everyone else get ranked, the fire inside me started to build and build, and when I got my cast off at the end of the summer, I went crazy every time I got on the court. I went bananas. I showed up to this elite camp in Providence and was killing everyone.

Pretty soon after that, I got my first scholarship offer, from the University of Florida. And then all of a sudden I was getting offers from Kansas, Florida State, Georgetown. Actually, I think the most surreal moment was waking up one morning to a missed call and then a text from a random number that said, “Hello, this is John Thompson. Hope all is well.”

An empty gym was my sanctuary. I used to go and shoot by myself at like one, two o’clock in the morning. On Friday nights when everybody was going to parties, I’d be in my little zone, headphones on, shooting from the rack. I remember one night, it was like three o’clock in the morning, and I was walking back from the gym. That Drake and Future mixtape had just come out, and I was listening to “30 for 30.” I guess I was going through something heavy at the time and, for whatever reason, that song just hit me a certain way.

I texted my mom on the way home, and I said, “Don’t worry. Pretty soon, you’ll never have to work again.”

I mean, I was coming off a freshman season where I averaged seven points. The NBA wasn’t even on the radar. I had no right to send a text like that. But for whatever reason, it was this really intense moment for me. I was going to make it happen, somehow.

A couple of weeks after that, I showed up to the gym at 1:30 in the morning. and I saw four of the nicest cars I’ve ever seen in my life in the parking lot. All blacked-out, parked side by side. It was weird. So I poked my head in the door, and I saw all these guys running a full-court pickup. But they had actual referees and everything. I’m looking … looking … then I’m like … is that … Rondo?

It was like a dream or something. Rajon Rondo was bringing the ball down the court in the Louisville practice gym at one in the morning. And then I saw Josh Smith and all these other guys who looked familiar.

And they were going hard. I didn’t even know what to say, so I just went back to my dorm. Then the next day, I ran into Larry O’ Bannon, one of the former Louisville guys I saw playing, and I said, “Did I just see Rondo here last night? What was that all about?”

Turns out Rondo would come and have these secret, invitation-only runs in the summertime, just on random nights. I was telling Larry every day, “Listen, you need to get me on that group text.”

Larry worked his magic and he got me in, and then one random night someone texted, “Who’s in tonight?”

And, man, I was so quick with the HANDUP EMOJI. Let’s go.

Rajon didn’t even really know who I was. He just knew I played for Louisville, so he was cool with it. But then, for whatever reason, he was always picking me to be on his team. Getting to run with him that summer was so valuable for me. More than anything, I realized how insanely competitive these NBA guys were. You realize it’s a mental thing for them. Like, it’s four a.m., and my opponent is sleeping right now, and I’m in a college gym running six, seven games straight.

At the start of that sophomore season, I was so mentally and physically ready to make the leap.

And then I didn’t. For some reason, I just didn’t.

Sometimes, life is like that. I don’t know why, but I got off to a rough start. It was probably the hardest two months of my life. I’ll never forget the lowest moment. I can tell you the exact date.

December 31, 2016. We had just gotten killed against Virginia, and I played terrible. We were playing Indiana at the Pacers’ arena, so all the NBA scouts were going to be there.

The night before the game, Coach told me that I wasn’t starting. It was super, super tough. I was in a really bad headspace.

But then I got a text message that I wasn’t expecting. It was from my sister. It was one of those texts that you have to scroll up to read — that’s how long it was. And we don’t typically talk this way. We usually keep it super fun. I mean, she was 13 years old at the time. But this message was just super heartfelt and honest, expressing how much she believed in me, and how she’d witnessed how hard I worked over the years, and how she knew everything was going to work out.

Then when I got called off the bench that day, I came out flying. I was hitting shots that I’ve never hit in my life — falling out of bounds and everything.

After that game, I just kind of never looked back. It’s really amazing to me how quickly everything happened. I’m sitting there on December 31, 2016, wondering if I was good enough, wondering if basketball was really worth it anymore. Fifteen months later, I’m in the NBA playoffs going up against Russell Westbrook. It definitely wasn’t supposed to happen like that, if you read what the experts were saying. But it was like that my whole life. I had people right before the NBA Draft, people I trusted, telling me, “I don’t know, I don’t think this is the right move. I don’t think you’re ready.”

I was in my head about it. I definitely didn’t want to leave Louisville. I had so much pride about playing there. But then I was playing against Paul George and CP3 and some NBA guys at a workout before the draft, and they both kept telling me, “You’re ready.”

I know guys in the league say, “Oh yeah, I love X, Y, Z city.” But man, I genuinely love Utah. The way that the city embraced me as a rookie is something that I didn’t even think was possible.

Everything happened so fast. The first game of the season, I’m supposed to be on the bench, but then Rodney Hood went out with an illness right before tip-off. So all of a sudden, I’m running out onto the floor. And who are we playing?

OKC. Russ. I have to guard Russ.

And it was so funny, looking back. Because I have this ritual in shootaround where I have to lock in on my opponent. I have to see you. It doesn’t matter who we’re playing — if I look you in the eye, and I get that visual out of the way, then I’m good. So I’m looking for Russ … can’t find him.

Of course, he always does that whole routine where he sits on the bench and he does his little dance routine, right? So I’m looking over to their bench, and big Steven Adams is standing there blocking the view. All of a sudden, he moves away, and I see Russ. He’s dancing. He’s doing his thing.

Then, out of nowhere, he turns his head, and I swear to you, he looked me dead in the eyes from all the way across the court. Dead in my eyes. It was like a movie. I froze. Everything kind of hit me at once, and it was like, Ohhhh, snap.

That was my Welcome to the League moment. I just kept telling myself, “Keep him in front of you. Do not let him dunk on you and yell in your face.”

Everything that happened in the first year in Utah was kind of surreal — from the dunk contest, to playing against Russ in the playoffs, playing against Harden in the playoffs, exceeding everybody’s expectations for what we could do. But for me, this second year was a lot more meaningful, because of how the city stayed behind me when I came out struggling.

More than anything, I want to have a lasting impact on this city and this community. One thing that I know just from my own personal experience is that this is bigger than basketball. My legacy has to be more than that.

When I was growing up, there were so many people who helped me get to where I am, and they didn’t want anything in return — whether it was my fourth grade teacher, Mrs. Pierce, who helped us out with clothes sometimes, or my friends from Greenwhich who used to pay for my lunch when we were out together, or my mom, who probably sacrificed more than my sister and I will ever know.

For me, everything comes down to a simple mantra: determination over negativity. So many people want to tell you what you can’t do. Especially now, with social media. But I think it’s important for kids to know that haters weren’t invented on social media. Haters have been around forever. AAU parents have been telling my mom she was doing the wrong thing since I was in third grade.

Oh yeah, and about that dream … Ever since I was in third grade and I walked into my friend C.J. Tyler’s house in Greenwich, I had this vision that I was going to buy my family a place of our own right next to my all friends. My mom probably wanted it to happen through a law degree or medical school or something like that, but we all have our path in life.

In the end, it happened through basketball.

My mom just moved into that house, and it’s right down the road from Greenwich Country Day.

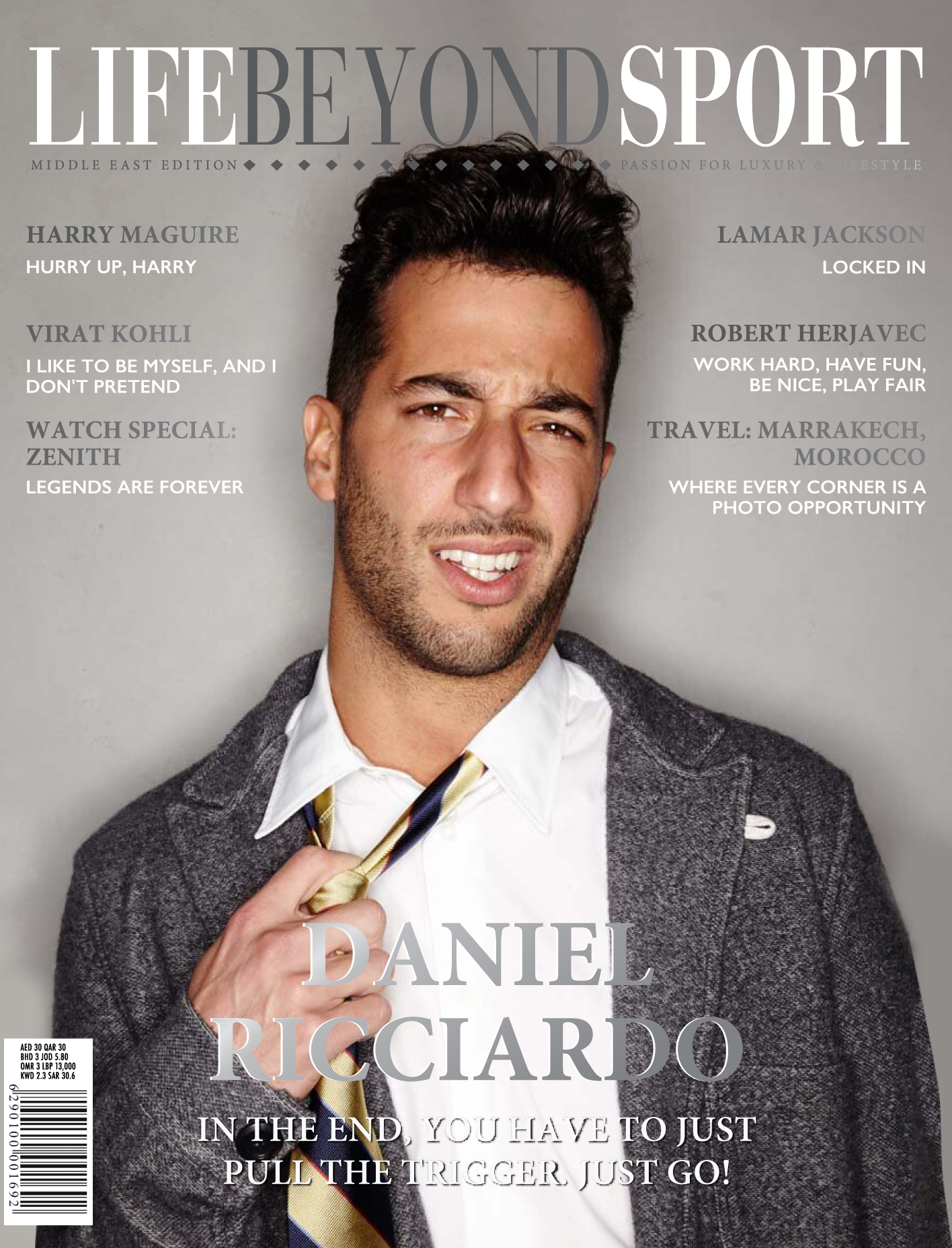

.jpg) Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.

Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.