Daniel Boulud is a French chef and restaurateur with restaurants in New York City, Palm Beach, Miami, Toronto, Montréal, Singapore, the Bahamas, the Berkshires and Dubai. He is best known for his eponymous restaurant Daniel, in New York City, which currently holds two Michelin stars.

Boulud was raised on a farm near Lyon and trained by several French chefs.Boulud built a reputation in New York, initially as a chef and more recently as a restaurateur. His management company, The Dinex Group, currently includes fifteen restaurants, three locations of a gourmet cafe (Epicerie Boulud), and Feast & Fêtes Catering. His restaurants include Daniel, Le Pavillon, Le Gratin, Café Boulud, Maison Boulud, Joji, and Joji Box, db bistro, Bar Boulud, and Boulud Sud.

Mr. Boulud, as a veteran of the nouvelle cuisine movement, what does this philosophy mean to you 40 years later?

In my restaurants today, I actually don’t think about nouvelle cuisine at all, but I do think of French cuisine. We take pride in our forager market: we always think local, seasonal, and we are very creative with that. Especially at my restaurant Daniel in New York. Of course, we welcome other cuisines into our menu and try to have a certain connection and authenticity to it, but we try to be careful not to divert, not to become too eclectic. In a sense, it’s very French, but with a mind in America.

In what way?

I think I’m surrounded by a very different world in New York than I was living in France, especially with the diversity of my team here in New York — if I am sitting around 12 French chefs, I think differently than if I’m sitting around a French, an American, a Hispanic, an Asian… For instance, when we arrived in Singapore to open a restaurant, we quickly noticed they love seafood there, so we definitely emphasized on seafood in Singapore more than we do in New York or London or any other place.

And what considerations come into play in your native France?

Well, if I were in France, maybe I’d cook differently! Because I grew up on a farm in Saint-Pierre-de-Chandieu, I think that’s what drew me into hospitality business. I grew up learning that you have to be hospitable in the kitchen, people come and see you, you offer them something to drink, something to eat. You never really welcome anyone without taking care of them. So I would help my grandmother in the kitchen, and then there was also the farmer’s market and a café where we would cook breakfast, lunch and dinner. I think we were writing the menu every night coming back from the market, because we knew exactly what we got that day.

That’s another benefit of the forager mentality you mentioned earlier — you know what you’re yielding and what you’re able to cook from these ingredients.

Exactly. And then there was always this cycle of harvest in which we would preserve our produce in order to eat our own food during the winter or during the summer so there was a lot of work done on anticipating and programming the shelf life of all the harvest too.

Was your goal to be both self-sustainable and environmentally sustainable?

Was your goal to be both self-sustainable and environmentally sustainable?

Absolutely. Everything and anything can always be recycled and made into a dish! Zero waste. I remember when I was young, I worked with chef Michel Guérard, and we would be travelling around the southwest of France, visiting local restaurants in the villages around La Gasgogne, and there was a restaurant where they were serving tripe. I knew that tripe was made with the stomach of the calf, beef, or lamb — but here, the tripe was made with the intestines of the goose. So I received this bowl that looked like shriveled and shrunk spaghetti, with onions and a brown sauce. It was very weird. I didn’t know what to think because I felt like, “God, should I eat it?” (Laughs)

Did you?

I did! It was super tasty, but a little funky. But coming from the countryside, I was not turned off, that’s for sure.

And regional French dishes can vary even from village to village.

Of course, that’s a very important thing. Even the making of food from home to home! When you live in a village, you’ll know which home has a good cook and which home has a bad cook! We were very discriminating against some of our neighbors who didn’t know how to cook. It’s funny because you will kind of eat the same type of food, but it is always different. Take something like goat cheese — there was not a single farm who had the same goat cheese! I mean, of course goat cheese is a personal interpretation of what you like about it, but we always felt that our goat cheese was the best of all of them!

It seems like that rivalry was crucial to your culinary upbringing.

Rivalry and pride always bounced together. But I think this reflects many other social observations in life! It doesn’t matter if it’s New York City or my little village, you always have that kind of rivalry and therefore the pride in what you do.

Did that hold true for the nouvelle cuisine movement?

No, actually. I really felt that in nouvelle cuisine, there was such camaraderie and such a shared passion for French food. At the time, French cuisine was maybe the only cuisine that really reacted to its tradition and its past, and transformed it. It was quite a revolution in France! The chefs were sort of leading the movement.

Chefs such as Michel Guérard and Alain Chapel?

Yes, but also Alain Senderens, Michel Troisgros, Paul Haeberlin — every one of them had an incredible background in classical French cuisine. There was a lot of study on how to make French cuisine lighter, more delicate and more presentable in the plate, and yet rustic and authentic. But most importantly, these chefs were travelling a lot at the time, and bringing a lot of new ideas from their travels. I think nouvelle cuisine opened the gate, and gave the opportunity to explore much further than just the French classic cuisine that we learned from these legendary chefs. In France, there is not a single region without a cluster of great chefs to learn from.

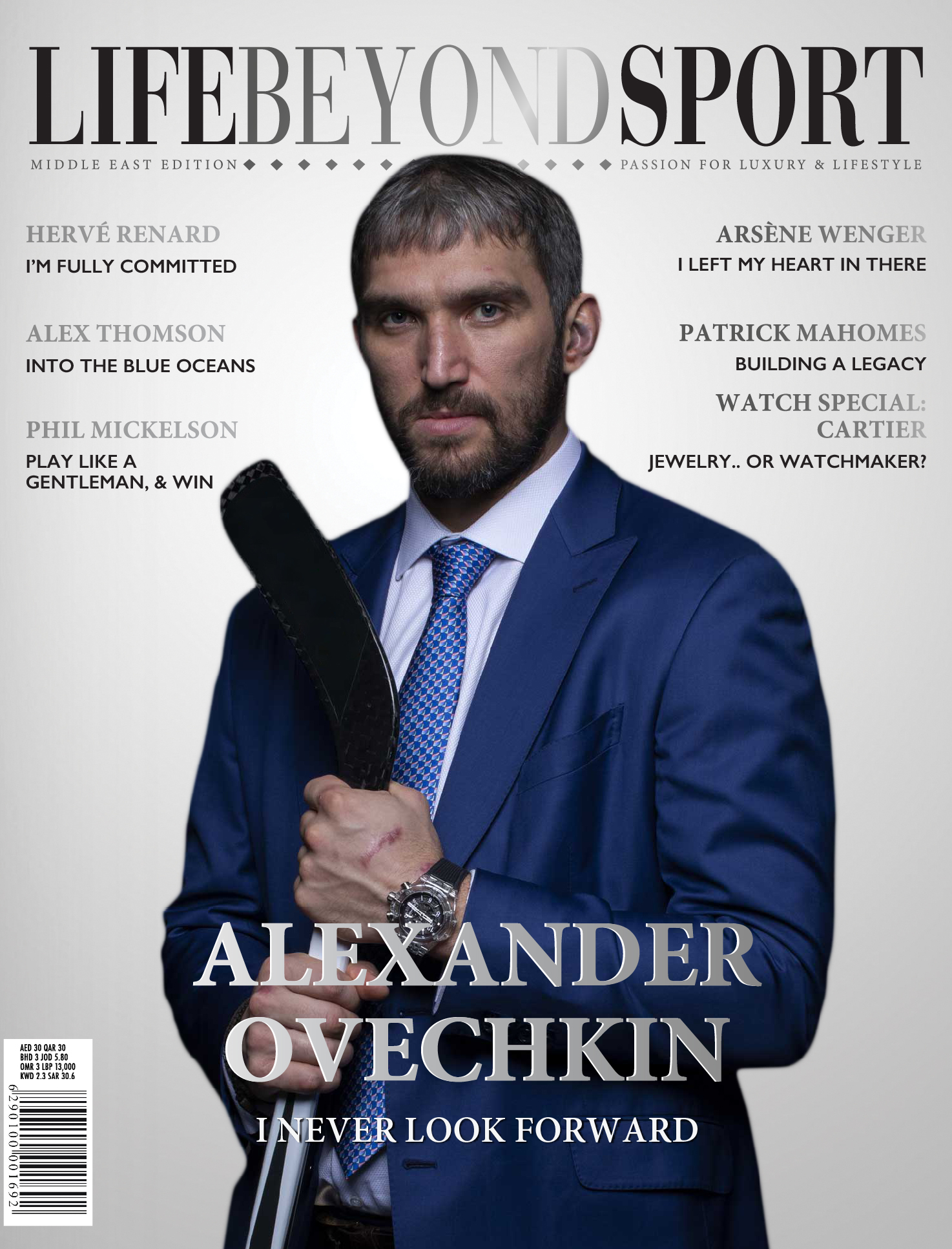

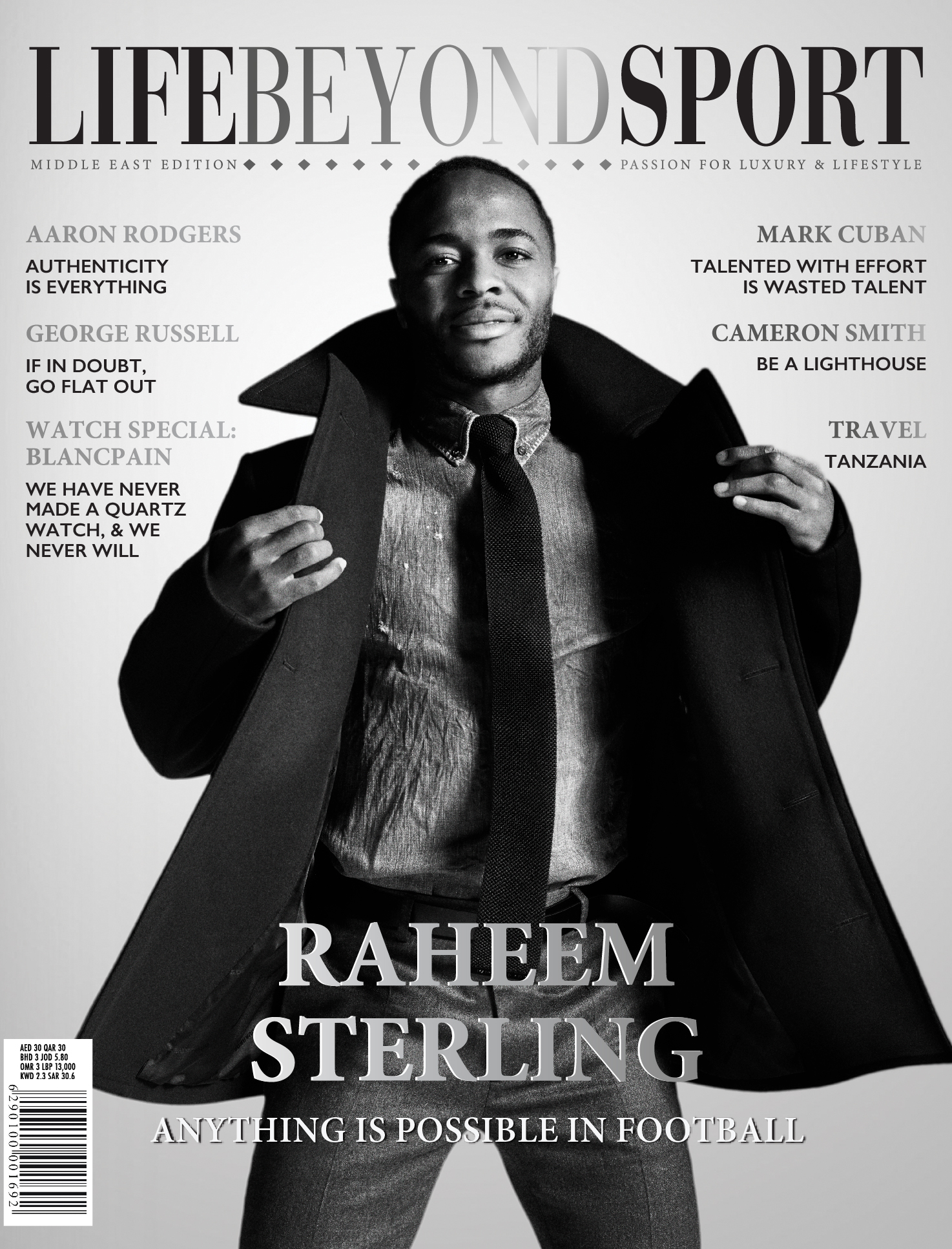

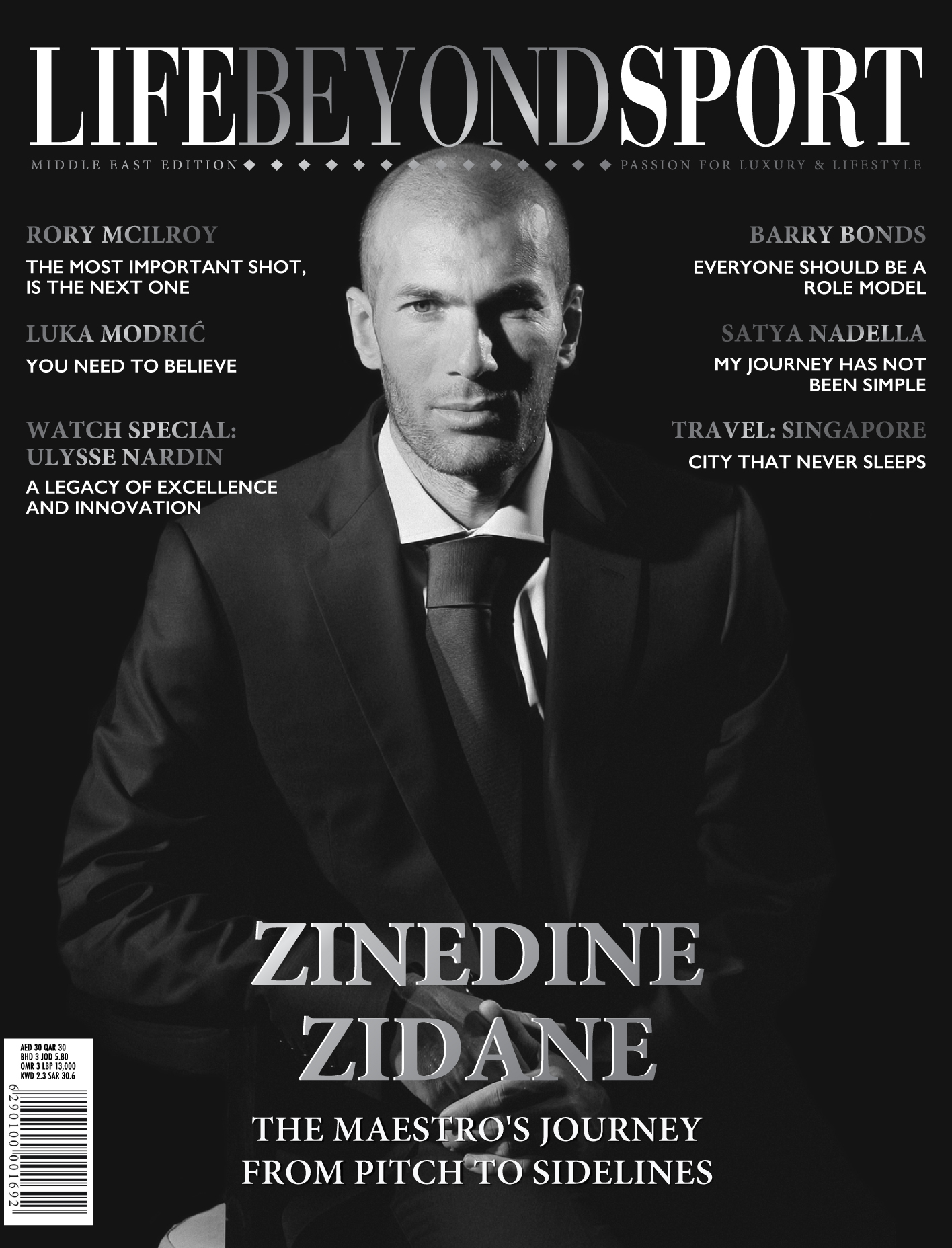

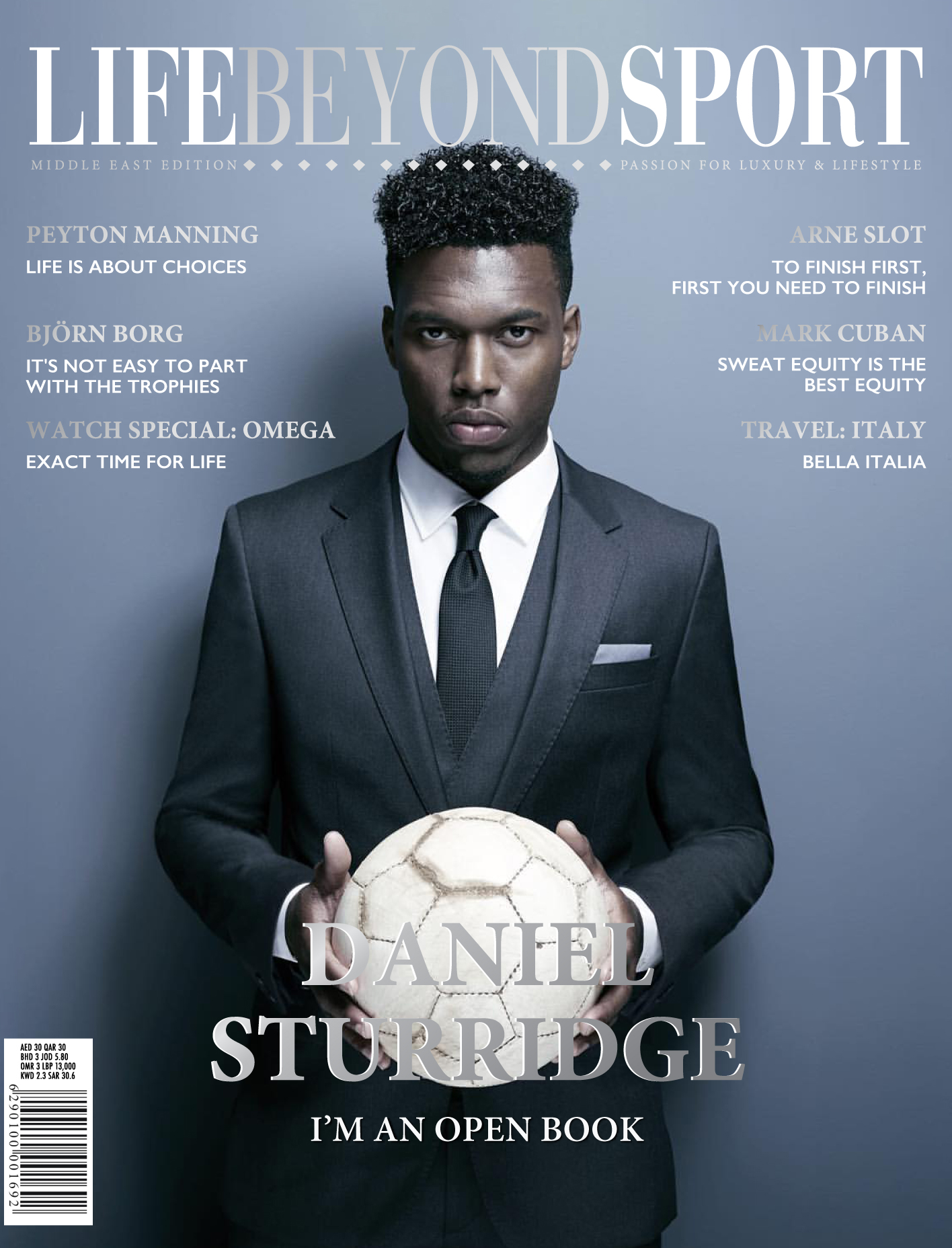

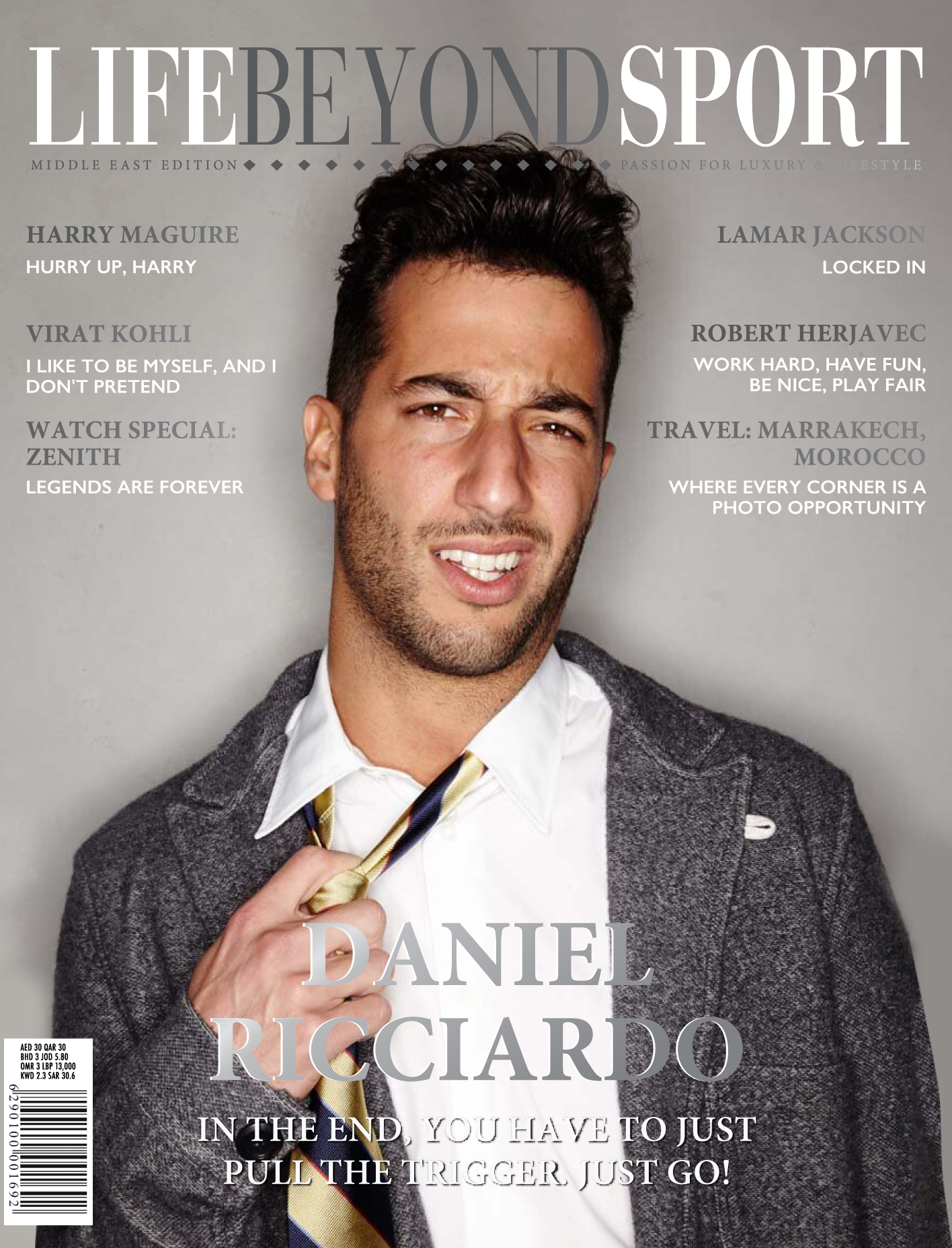

.jpg) Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.

Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.