He has played in a European Cup semi-final against Real Madrid, the team who owned him, before 78,000 at the Bernabéu; in consecutive Champions League finals, against Barcelona in front of 70,000 at the Olympic Stadium, Berlin and against Atlético Madrid in front of 61,000 in Lisbon; and at the Stade de France, Paris, standing before 76,000 fans and the men who warned him to wear a helmet. But Álvaro Morata says he was most scared the night he stood in front of barely 1,000 people at the Teatro Calderón, Madrid – even though, that night, everyone was on his side.

TEXT: LIAM TWOMEY // PHOTOGRAPHY: HUGO BOSS

Alvaro Morata said that he is seeing a psychologist to help him deal with the "pressure and emotions" he experienced at Chelsea last season, adding that he briefly thought about leaving purely to join a club where he could play "without pressure."

Chelsea paid a then club-record £58 million to sign Morata from Real Madrid as Diego Costa's replacement in the summer of 2017, but he faded badly after a bright start as injuries and off-field events -- his close friend was killed in a car crash and his wife endured a difficult pregnancy with the couple's twin boys -- sapped his sharpness and confidence.

"I think it's very important to have confidence," Morata said. "Things go well for you. In this period of my life I have realised that you always have to train your mind. It's not only about being physically prepared. To withstand the pressure, you also have to work, it is the most important thing in our field.

"I had never thought about training the mind, really. When a player hears the word psychologist at the first, you are taken aback, but I realised that I needed help.

"At first, I was a bit embarrassed to talk to the psychologist and tell him all my problems and with the help of everyone I have managed to recover happiness in football.

"The idea of going to the psychologist, for anyone who has any problem, is associated with something negative. I think everyone sees it that way when it's really a very important thing. Now I am happier than ever, even if it is not my best moment on the pitch.

"I've scored goals again, but it's not when I'm playing my best football. I will continue going to the psychologist, it helps me to manage the pressure and emotions."

During a show conducted by the magician Antonio Díaz – “El Mago Pop” – Morata was called on stage with his then girlfriend and now wife, Alice Campello. Díaz made Alice face one side of the stage, telling her: “This’ll be the best trick you’ve ever seen.” She turned back to find Morata on one knee, ring in hand. “I was more nervous that day than any other,” he says. “When you’re taken away from your pitch, your territory, the nerves are greater.”

There is something in that line, coming from a 26-year-old in whom some have seen vulnerability even on his territory and who talks honestly about pressure, insecurity and fallibility. Morata engages with the psychology of football in a quiet, considered voice, expressing a simple but often forgotten fact: players are people too. Sitting there, gently pulling the cuffs of his training top, Morata discusses talent and ambition, success too, but conversation also drifts to the dark side, to frustration and uncertainty, the bad times to be overcome. Which is where Alice comes in.

Morata had joined Juventus from Madrid for €20m, aged 20 (signed by Antonio Conte, who left the same summer to manage Italy). He won the double in his first season as well as scoring in both legs of the semi-final and again in the final as Juventus finished runners-up in the Champions League. But in his second season, he was struggling, 100 days passing without a goal and he had tried everything, from cutting his hair to changing car. Things were not right; he wasn’t right. “People think we’re machines; they don’t realise that behind a bad run there’s almost always a personal problem, some family issue,” he says. “You have feelings, you make mistakes, you’re a person.”

“I was a bit lost. It wasn’t just the goals; I was arguing with people who are important to me, not bothering with things that truly matter,” Morata continues. “It was a bit of everything. I’d left home young, I’d fought to play for Juventus and I was ‘conditioned’ by Madrid having a buy-back option that didn’t depend on me. I didn’t know my future. All that affected me and I let myself slide a bit, became distracted.”

Morata was down, his mood impacting his play. It did not go unnoticed. “I’d just finished training one day. It had been a terrible, terrible session – one of the worst in my life. I couldn’t even control the ball. The physio asked what was wrong and I told him I was sad. I was crying. I was there on the treatment table and Gigi Buffon was next to me. Afterwards he took me aside, alone, and said that if I wanted to cry, do it at home. He said the people who wished me ill would be happy to see that and the people who wished me well would be saddened by it.”

“I was lucky: I met Alice and my life changed. We’re going to get married. Thanks to her – you never know what might have happened had she not come along – and to me too, I got back on track, felt important, scored goals. Now I’m better prepared to play at the highest level. I feel that more with every passing day.”

Buffon always thought he could, claiming Morata had everything to be among the world’s best “if only he could get over his mental hang-ups”. Morata describes the legendary goalkeeper, who has played over 1,000 games, as like a father, the gratitude palpable, and insists Buffon sought to protect and toughen him. He also believes this was not about enemies within, but opponents detecting weakness on the pitch, admitting: “They could see my head go down in games.” Yet hearing the conversation recalled, it’s difficult not to be drawn to it. And if Morata moved beyond those dark days, some of the issues remain.

Buffon’s advice paints a harsh portrait. Is football so unforgiving, weakness so preyed upon? Was Morata especially vulnerable? Is he? Alice arrived and he says he has matured but talking to him, sensitivity shows. That experience, a realisation of football’s realities, make him even more interesting company. Morata is intelligent, introspective, unusually willing to discuss aspects of the game that are not just the game – and which he believes have impacted his career.

“Sometimes I go home, put the game on and think: ‘How can I miss that?’ It affects you; it also affects you to know your career also depends on the opinion of journalists, fans, directors, and sometimes they’re not really qualified to judge. In my position, what matters is goals. ‘Did he score? No? Una mierda de partido [a shit game].’ They don’t know the movement, everything you’ve done. Your life can change in a moment, depending if the ball goes in. In a week, I went from people shouting, ‘Leave Madrid!’ to scoring against Sporting and then, ‘Hey, saviour!’ You can’t think you’re God when you score an important goal or the worst player around when its going badly.”

“But,” he says, “when the ball starts to roll, that rescues everything. Thankfully – because if not, it would be more of a business than a sport & hobby to me.”

It remains a business, though.

“I made my debut young with José Mourinho, but if you wait two more years you’re not so young: it’s seven years now. I have to take off now. I have to play every Sunday, but that doesn’t only depend on me.”

So, what if the phone goes again, the Premier League on the line? If Chelsea call back? If the season ends with no sign of change will he say he needs to go? “I can say that, but …” he starts. He knows they may not listen. “I’m happy at Atletico and they support me,” he says. “But if an offer like that came again and they want to sell, I shouldn’t close doors. I loved all the countries that I’ve played in, but if one day I have to leave, I’m sure it will be to the Premier League again.”

It is not just the league, the country, it is something else, too: a thread that runs through the conversation is confidence, the need to feel needed, appreciated, secure. “Conte is the manager who most ‘bet’ on me, without even ever having had me in his team,” Morata says. “I’m very conscious of that: he bet on me for Juventus but left before I arrived; then he wanted me at Chelsea come what may. He knows me better than I could imagine, I’m sure, and that’s important: it motivates you to work hard, train well.

“I feel indebted to him because he’s the coach that most trusted in me, most wanted me, who made me feel I could perform at the highest level. And I’m happy that I’ve been able to play for him. To be able to give something back. The future excites me, whether that’s Atletico Madrid or somewhere else. I still have to learn, improve. I can do a lot but I need to play more and for someone to really back me. Either I take off or I end up in a position of comfort, playing games occasionally. I’m no longer the youngest, I’m 26, it’s a big moment.”

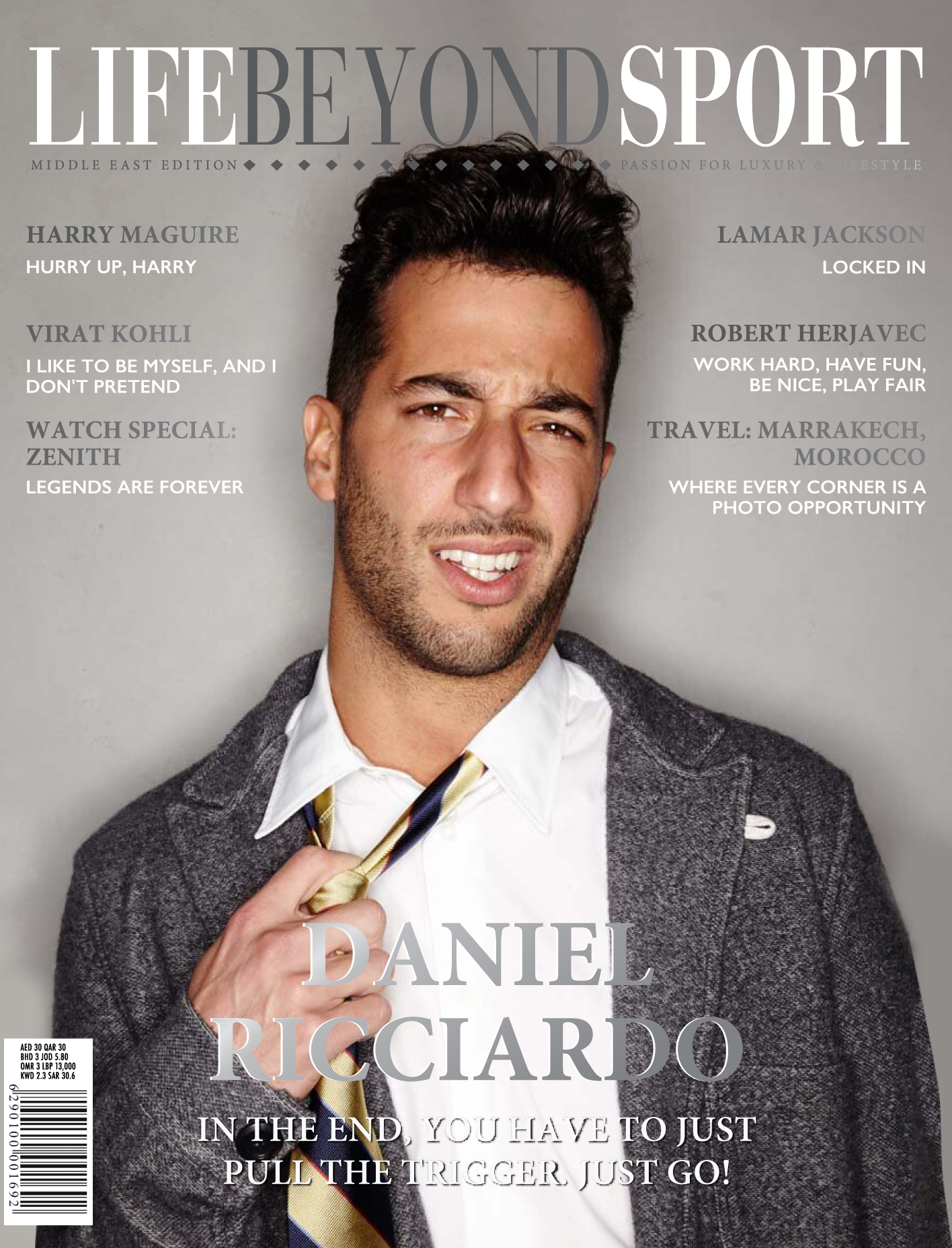

.jpg) Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.

Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.