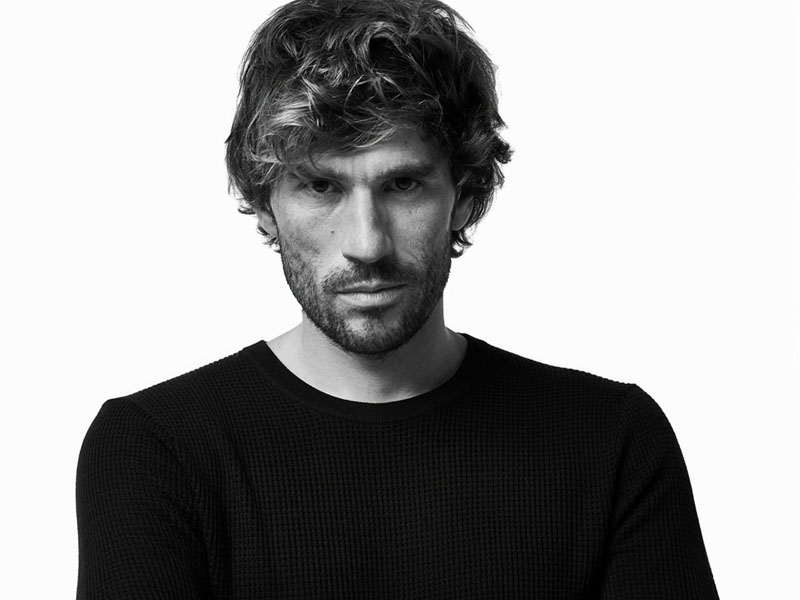

In an interview with SPIEGEL, French free diver Guillaume Néry discusses the dangerous pursuit of world records, the art of holding his breath for up to eight minutes and how diving can help humans rethink their relationship to water.

He has explored the depth of the unknown, and in it found the limits of humanity.

Mike: How did you get into freediving? What attracted you to the sport?

Guillaume: I discovered freediving by chance, doing a challenge with a friend on the bus to school. We were just trying to hold our breath the longest. I was 14 years old, and this was an experiment to [find] the limits of my body. That was fascinating to me. Because I was living in Nice, by the Mediterranean Sea, I decided I should try [doing it] underwater. It was much more interesting than just holding my breath on the bus! I fell in love with this feeling of going down deeper and deeper, like I was discovering an unknown planet. Today, the quest of the unknown, the exploration of human limits—these are still my passions. But lately I’ve [used] freediving for reconnecting with my own body, getting this harmony between the body, the mind, and the water. I don’t need to compete or break a record to experience it. Every time I go underwater, it feels like a moment of peace and happiness, whatever the time or the depth. Of course, as an athlete, I like world record attempts or world championship dives. I have prepared for so many hours, days, weeks, months, and you just have one chance to make it perfect. That’s the most challenging part. Freediving is all about relaxation, letting go, but it’s very hard to relax when you know you are about to attempt the deepest dive ever. In the end, the most enjoyable thing is when you can forget about all that, and just focus on the great feeling of gliding in the water.

Mike: Guillaume, when you dive, you venture into places that are extremely inhospitable to human beings. There is no oxygen, the water can be as chilly as 12 degrees Celsius (54 degrees Fahrenheit) and it is pitch dark. What is the appeal?

Guillaume:: You are mistaken. It's not at all dark down there.

Mike: What is it?

Guillaume: It is more like a deep, intense blue all around me. Only in the deep can human beings experience the meaning of infinity. And if I want I can move in any direction -- up, down, left or right -- I feel free in a way I never could be on land.

Mike: The best pearl divers reach depths of 45 meters (148 feet). But you manage depths of well over 100 meters without oxygen, and the aid of only weights and fins. It's a journey into a death zone. If you become disoriented or panic, there is no rescue. How do you prepare yourself?

Guillaume: I put myself into a relaxed state. It should be roughly like the feeling you have after getting up in the morning, when you are still a bit tired, not entirely awake. Before going down I lie still on the water and try to become part of this element. Just before diving down, I inhale as much air as possible.

Mike: How many litres of air fit in your lungs?

Guillaume: About 10.

Mike: A normal person has a lung volume of six litres.

Guillaume: Using a special breathing technique I can compress the air in my lungs like in an oxygen cylinder. That allows me to fit more inside. But even more important than the amount is the fact that I use as little oxygen as possible while I am diving. I have to utilise the available air as well as I can. I have to be efficient, like a fuel-efficient car.

Mike: What happens to you on the way down?

Guillaume: Within a few meters, the diving reflex sets in -- this is an effect we humans share with whales or dolphins. My heart rate drops and the blood flows to my heart and my head, to the most important regions. My body switches into economy mode, so to speak. Beyond 35 meters the pressure is so great that I sink automatically. I stop moving and just drop into the deep -- a spectacular sensation.

Mike: At 115 meters, your lungs are extremely compressed, the size of two oranges, and filled with only a half litre of air. Is that still a spectacular feeling?

Guillaume: At this point the gases start to dissolve in your blood. That has a slightly narcotic effect, a form of intoxication. Perhaps it's a bit like after drinking two beers, when you are a little bit drunk but still have everything under control.

Mike: How often does your heart beat at this depth?

Guillaume: No devices exist yet that can withstand the pressure to measure this. But I would estimate it comes to 20 beats a minute.

Mike: At that depth, a pressure of 13 kilograms (29 pounds) acts on every square centimeter of your body. You don't wear a diving mask because the pressure of the air between the mask and your head could suck out your eyeballs. How do you deal with such conditions?

Guillaume: I have been training for 14 years. I have done several thousand dives in my life. As a result, my body has adapted very well to the deep. I have learned to accept the pressure. I experience no pain down there.

Mike: It is said that the way back to the surface is harder than the way down. Why?

Guillaume: Because I have to keep swimming all the time in order not to sink further. That is tiring and consumes a lot of energy. I reach the critical point just 10 meters below the surface. By then my body is burning, it is acidic like after a long sprint and produces a lot of lactate. In order to break that down, it withdraws the remaining oxygen from my blood. If I have budgeted well, I have enough reserves.

Mike: And if not?

Guillaume: If I do lose consciousness, the safety divers will pull me up. They accompany me for the last 30 meters.

Mike: What does the first breath after reaching the surface feel like?

Guillaume: Pretty good. That's what I imagine the first breath to be like after we are born. My lungs expand; I feel alive. I like that moment very much.

Mike: Your dives last up to four minutes. Those who do another competitive diving discipline called 'static apnea' lie face down in the water holding their breath. The best can exceed eight minutes. How does one suppress the breathing reflex for so long?

Guillaume: It is a matter of concentration. I first have the urge to breathe after four minutes. There is a tugging in my throat. But I have trained myself to suppress the feeling for another four minutes, while remaining calm at the same time.

Mike: Would you like to remain underwater for longer?

Guillaume: Sometimes at night I dream of diving. I am in the sea and never have to go to the surface for air. That's wonderful, but it has nothing to do with reality.

Mike: People aren't fish. At more than 100 meters deep with no technical help, they are out of their element. Does the danger appeal to you?

Guillaume: I would never take a risk. Before a dive I listen inside myself, and I go into the water only if my body signals that everything is fine. I pay meticulous attention to safety, and I always have a team around me to intervene in an emergency.

Mike: Have you ever had any serious problems?

Guillaume: Yes, during my third world record attempt at Nice in 2006. I wanted to dive down to 109 meters. Lots of media were there, sponsors, my family. I had to succeed on that particular day and that put me under stress. A few metres before reaching the surface I fainted. A safety diver pulled me up. In 2015, I was trying to break my fifth world record, attempting a dive at -129 meters. The organisation made a mistake on the rope measurement, and I dove at -139. It was of course too deep, and I lost consciousness a few meters from the surface [during the ascent]. It could have been very serious. I recovered after few days, because I was in a very good shape.

Mike: Sometimes it still goes horribly wrong like it went wrong with Belgian former world record holder Patrick Musimu. He died during training. During your training camp in 2015 the Arab champion, Adel Abu Haliqa, did not return to the surface after diving to a depth of 70 meters. His body has been missing ever since. What happened?

Guillaume: We are still trying to reconstruct the accident ourselves. Adel allowed himself to be dragged down by a sled. He then seems to have released his safety hook from the rope on which he dived down. We don't know why. We can only accept his death, not explain it.

Mike: After the accident, a robot searched the seabed for Adel Abu Haliqa for days. Your group went on training. Is that your form of acceptance?

Guillaume: It isn't that simple. We were all shocked. But it is important to go back into the water quickly after an event like that.

Mike: Why?

Guillaume: In that situation, I need the reassurance that diving is a good thing for my body. If I had taken a break, I would have spent days dwelling on it. The sport would have become something that took away a friend. In that case, I could have ended my career then and there.

Mike: French world record holder Loïc Leferme, your best friend, died 12 years ago during a dive. Did you think about quitting then?

Guillaume: Yes, of course. After his death it took me a year and a half before I rediscovered my passion for diving.

Mike: Both accidents happened in the 'No Limits' discipline, where a motorised sled pulls the diver down into the deep and an air-filled bag brings him back up again. Is that sport or megalomania?

Guillaume: I used to train using a sled, but never deep. We use it in our free-diving club in Nice (CIPA) as a toy to play around 40 meters. I never did serious stuff deeper than 80 meters because you cannot get back up again on your own. Your life depends on technology. That's not my thing. I want to be in sole control of my dives.

Mike: Despite a number of such accidents in recent years there has been an ongoing quest for world records. Why do you and your colleagues continue to take such risks?

Guillaume: We are professionals and we train hard every day. The attempt to be the best is simply part of this adventure. It is part of the game, a game for grown-ups.

Mike: You market yourself as a kind of underwater artist. In a hit YouTube film called 'Free Fall' you jump into the world's deepest underwater sinkhole, the 202-meter deep Dean's Blue Hole in the Bahamas. You have been photographed diving with dolphins, and recently did an underwater photo shoot in which you wore expensive haute couture clothing. Why do you do these kinds of productions?

Guillaume: Through my work I want to show that you can feel just as comfortable in water as you can on land. Many people have this fear of the open sea or of the deep, which is totally unfounded. I would like more people to go into the sea again. Unfortunately many people today view the oceans as a source of income. They suck up oil from the sea floor and deplete our waters of fish. They have lost their respect for water. We really must rethink our ways.

Mike: In September you are taking part in the world championships in the bay off the Greek town of Kalamata. How deep can a human being dive without an oxygen tank?

Guillaume: In 1960, doctors said we would never get beyond 50 metres. They underestimated the incredible capability of the human body to keep adapting further and further. Free-diving is a young sport and systematic training has only been around for 15 years. We are still a long way from the limit.

Mike: Thank you for the interview, Guillaume.

TEXT: MIKE HORN // PHOTOGRAPHY: FRÉDÉRIC PELATAN

.jpg) Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.

Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.