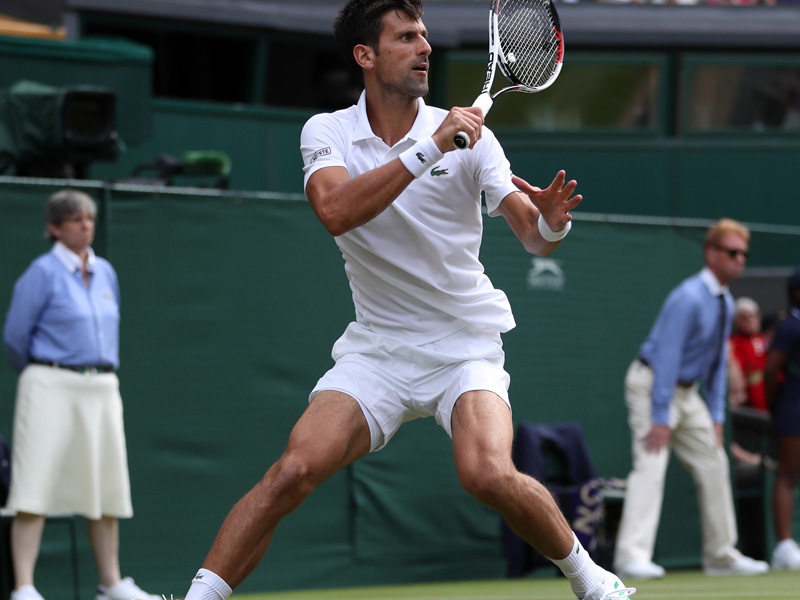

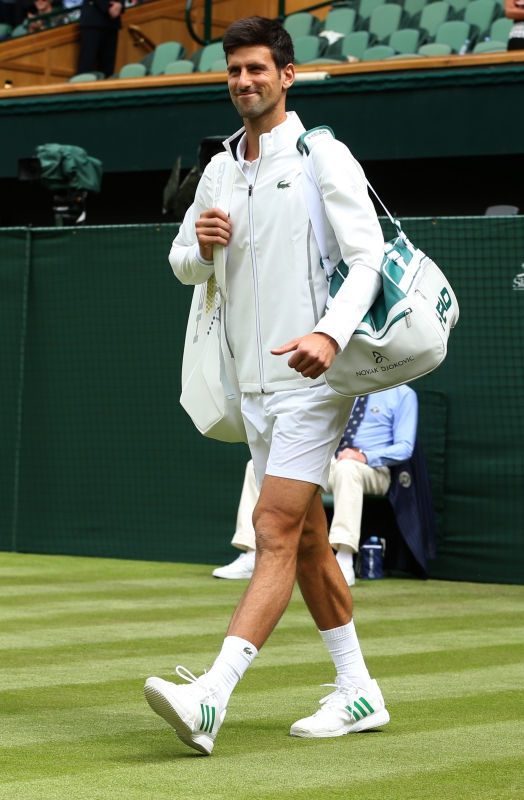

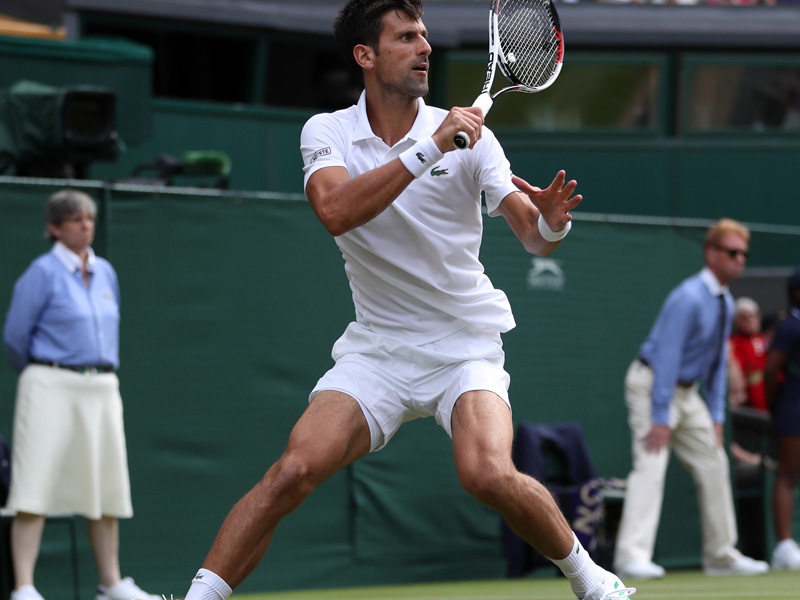

''Just walk like this, enjoy,’' Novak Djokovic says. Our interview was supposed to be conducted on a tatty sofa but Djokovic is sweating after a morning workout, his nostrils flaring as he pumps the air back into his chest, and he doesn’t want his muscles to stiffen. So we stride back and forth talking about his new Lacoste collection, and giving us a glimpse into the crowded life of one of the world’s best tennis players.

The aquamarine waters, gilded casinos and general high-rise glamour of Monte Carlo don’t immediately conjure any sense of sportiness. The mood is languorous; bodies stretch out on loungers, super-yachts stalk the horizon and the most rapid-fire inter -actions revolve around credit-card terminals and the roulette table. That is until you wind a path to the Monte Carlo Country Club on the clifftops above Roquebrune-Cap-Martin.

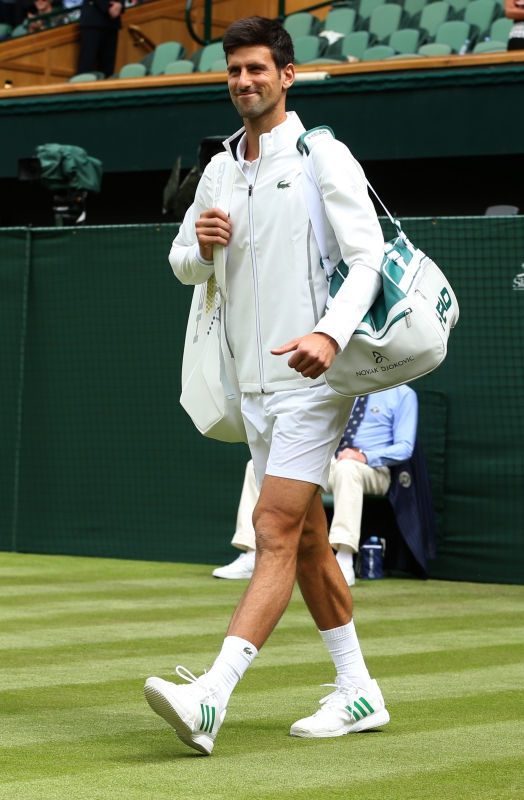

Here, Novak Djokovic bounds forth, lean and athletic in a slim-fit blazer and polo shirt, crackling with energy. The outfit, preppy but sports-centric, is no accident: Djokovic has partnered with Lacoste to launch a collection of clothes that bring the heritage and history of the brand – founded in 1933 by tennis champion René Lacoste – up to date with vivid designs, splashes of vibrant colour and a focus on technical fabrication, including ergonomic stitching and perforated sections for ventilation. The range encompasses functional tennis polo shirts and shorts, as well as athleisure staples in the form of zip-up tops and sweatpants.

"René Lacoste was a revolutionary in two senses: he changed the game of tennis and he changed fashion. That’s why I was so curious about the brand and what we could work on," says Djokovic. Where fresh whites tend to dominate, the new collection also focuses on a graphic grid design and block shades, the tones of which are meaningful for the Serbian, who now splits his time between his home country and Monaco (where he owns an organic juice bar). "My father would wear Lacoste polo shirts when I was a child. I remember his drawers had stacks and stacks of polo shirts, all in different colours, so it’s nice for me to be able to revisit my dad’s wardrobe and update it a little bit."

Like Serena Williams insisting her shoes are laced a certain way, or Andre Agassi (who now coaches Djokovic) playing commando, the tennis champion subscribes to the belief - perhaps superstition - that what one wears on court carries certain talismanic power. "Psychologically, the colour of what I wear is very important. I like the idea of camouflage, and always try and pick the colour that is closest to the shade of the court. It makes me feel compact, aligned and connected to the court and its surface," he says. "Tennis is a dynamic and fast sport: everything happens in the blink of an eye, so you need to feel like you’re part of your surroundings. What I wear on court is important to me. It changes how I feel and the energy around me."

It was René Lacoste’s innovations in design that meant traditional attire for tennis (Oxford bags, flat caps) was done away with. Long-sleeved shirts relaxed into the jersey-fabric polos we know today, with collars softened instead of starched. The crocodile emblem is a nod to his nickname after a bet that saw him winning a crocodile-skin bag. He also invented the lightweight metal tennis racket. It was that sense of dynamic experimentation that drew Djokovic to the brand - he has spoken about delving into new-age spirituality as a method of mentally preparing for games.

Djokovic’s regime, as one would expect, borders on the monastic - daily rituals of yoga, meditation, no gluten, no dairy. It’s his birthday today, but there’s no question of tucking into the champagne and trays of petits fours on offer. "I remember hearing something that Lacoste said and it stuck with me: “Playing and winning without style is not enough,”’ says Djovokic. "He was referring to fashion, but also to character and a respectful behaviour on court. That’s something I believe in."

One minute Djokovic is acknowledging the open-mouthed stares of a passing tour group, drawing a ripple of awe as he offers a cheery 'buongiorno’. The next he has to jump right back into the interview to continue talking about his life and future plans.

Clearly, this is no ordinary sportsman. Wielding a racket has never been enough for Djokovic. When he first joined the tour, he was known for his japes and impressions of other players, which contributed to his early reputation as a pushy young punk. They also put people’s backs up in the locker room, which explains why he shelved his former persona – the Djoker – soon after his 20th birthday.

Now, almost a decade on, he has grown into one of the sport’s most bankable performers, as well as a statesman with a strong nationalist agenda. It makes perfect sense that he should identify with the Serbian inventor and scientist Tesla – an underappreciated figure, in his eyes, whose glory was unfairly eclipsed by Edison’s stronger commercial instincts. This is a man, after all, who has spent his whole career in the slipstream of Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal.

'Nadal and Federer were the first two players to really cross over into the sporting mainstream,’ says Mats Wilander, a serial champion of the 1980s who now follows the tour as a broadcaster. 'Novak doesn’t have the same respect as them – yet. Those two did such a great job of taking the game outside its regular space: the lifestyle, the look, the fact that you know what you’re going to get every time they go on court. It’s like a Stones concert. I see Novak more as an indie artist – he has an unpredictability about him, and his fans are diehard fans.’ Some great athletes arrive fully formed, like meteors falling from the sky. Not this one. In 1999, at the age of 12, while his exact contemporary and future rival Andy Murray was winning the prestigious Orange Bowl in Miami, Djokovic was just another 5ft wannabe with a racket that looked too big for him. That summer, his parents begged, borrowed and scraped together enough money to send him to a tennis academy near Munich. Its founder, the former Wimbledon semi-finalist Niki Pilic, had little inkling that he was looking at a future champion. 'He was moving OK,’ Pilic recalled recently, 'his coordination was OK, his serve was OK but nothing special, and he didn’t volley much.’

Yet this assessment failed to take into account the young Djokovic’s greatest asset: his flexible and inquiring brain. Before mindfulness had become a cliché, he was already experimenting with meditation and self-awareness. The subject is exhaustively explored in his 2013 book Serve To Win – a classic example of his refusal to follow the pack. Instead of releasing a memoir like everyone else, he came up with a zany mixture of autobiography, self-help guide and cookbook. Its subtitle – 'The 14-day gluten-free plan for mental and physical excellence’ – alluded to the dietary shift that saw him abandon his beloved pasta and pizza in 2010, with the result that he lost 3kg as well as his reputation for fading towards the end of five-set matches.

Djokovic’s own journey towards 'mental and physical excellence’ had begun in 1990s Belgrade, as Yugoslavia collapsed into ethnic conflict. War-torn Serbia was hardly the ideal starting point for a would-be champion. At one point in 1999 he spent 78 nights huddling in a bomb shelter with his family. He emerged only to hit balls on the site of the most recent attack, on the basis that the Nato planes were unlikely to strike the same place twice running.

His training partner and mentor in those days was the former Yugoslav national champion Jelena Gencic. They had met six years earlier, when Gencic was running a tennis camp across the road from the Djokovic family’s pizza parlour in the ski resort of Kapaonik. A solemn little boy arrived one day, carrying a backpack and a racket, and pressed his nose up against the chain-link fence. In an interview with Djokovic’s biographer Chris Bowers, Gencic remembered 'his ability to keep his eyes focused on me when we were talking. It made me think right away that this was a very unusual boy.’

'We talked about life in general,’ Djokovic recalls now of the seven years he spent with Gencic. 'Not just how to hit the inside-out forehand or backhand down the line. We talked about classical music, we talked about poetry, we talked about everything. She kind of behaved like my mother. I owe a lot of gratitude to my own parents because mums all over the world are overprotective of their children, and I was the first son in the family. Obviously I needed permission from my mother to spend this private time with her and to actually have her support me.’

With his usual questing intelligence, Djokovic has sought out some unusual solutions to the hurly-burly in the past. During his trips to Wimbledon, he is a frequent visitor to the Buddhapadipa complex – which describes itself as the UK’s first Buddhist temple – a few minutes’ walk from the All England Club. 'I like spending time in the park and hearing the peaceful sounds of the water and seeing people just relax and connect to the nature.’

The Buddhapadipa is not used to hosting multi-millionaire athletes, but then Djokovic is hardly a typical example. You won’t find too many footballers who read up about electrical engineering, publish cookbooks and practise transcendental meditation. Even when he turns his inner Leonardo off and sits down to watch TV, he is still monitoring himself for signs of his greatest enemies: negative energy, and – even more chilling for his opponents – wasted potential. 'Flash, that’s the show my wife and I are watching now,’ he says with a laugh. 'It’s an American TV show, a kind of superhero thing. You need to have a filter, something that gets your mind off the tennis and just relaxes and recharges your batteries, so the next day you can be motivated to practise and do the same things over and over again. Because if you are completely in it, if you don’t have a social life, if you don’t have other interests, it’s very hard to maintain this will to win.

'It’s like yin and yang,’ he concludes. 'In life it’s all about balance. If you want to reach the biggest heights in such a demanding sport you need to be able to holistically approach everything and satisfy your needs – emotionally, privately, professionally. Now I am committing myself, not just as I did for most of my life to tennis, but to my family, to my wife and my baby, and to really be able to win the battle over my own ego.’ This is no ordinary sportsman.

TEXT: STEPHEN DOIG // PHOTOGRAPHY: LACOSTE

.jpg) Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.

Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.