Life Beyond Sport’s Imogen Lillywhite was among a select group of journalists who were invited to experience the very heart of Jaeger-LeCoultre’s watchmaking history - its headquarters in the tiny village of Le Sentier in the remote Swiss Vallée de Joux - as part of its 180th anniversary celebrations.

In a world that is caught up in a perpetual fascination with new technology, luxury watchmakers have a challenge on their hands holding the interest of consumers. While it is true that high-end horologists were in the doldrums in the late 20th century thanks to the onslaught of digital technology, the best adapted in order to survive and secured the affections of those who love watches as symbols of wealth, objects of beauty, and examples of man’s continuing quest for innovation in its purest form.

One of those watchmakers is Jaeger-LeCoultre, a brand celebrating its 180th anniversary this year, which, although owned by Swiss luxury conglomerate Richemont since 2000, has retained an independent spirit and a true sense of the traditions that founded it.

Jaeger-LeCoultre’s roots are in the Vallée de Joux, which borders France. The valley is home to not just Jaeger-LeCoultre, but several other high-end watchmakers and it is jokingly referred to by the Swiss as “The Siberia of Switzerland” due to the fiercely cold winters. It is this climate that fans of horology have to thank in part for the area’s extraordinarily high concentration of watchmakers as it was the bitter winters that drove farmers indoors and in search of another form of income in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

The brand was founded in 1833, although it only came to be known by that name later, by Antoine LeCoultre, the descendant of French Huguenots who had fled religious persecution. The LeCoultres settled first in Geneva and then later in the Vallée de Joux, which translates literally as “Rock Valley”.

Fast forward more than two centuries, and, the settlers discovered metal deposits close to the surface of their land, which they began to work with, making wheels, then more sophisticated items like music boxes, and eventually, watches. Antoine’s workshop is still remembered in the Jaeger-LeCoultre headquarters of today. The Manufacture is a place which hums with the history of nearly two centuries of watchmaking, as the high-tech facility is on the same site as that first small workshop, which became LeCoultre & Cie and later, thanks to a partnership with Paris-based watchmaker Edmond Jaeger, Jaeger-LeCoultre.

This partnership corresponded with the time when wristwatches, previously the preserve of women, began to become popular with men. While previously pocket watches had dominated, wristwatches became popular among men in the military during the First World War and entered the mass market.

Marina Shvedova, a brand spokeswoman explained some of the history of this most fascinating of family businesses during a tour of the Manufacture: “The valley is very isolated. We are very high up in the mountain, with all the modern equipment today we can exchange information immediately with every part of the world. In the early 20th century, it was so isolated, a forgotten place in the world.

“Producing watch movements here, we would not know what the clients would want around the world. We needed someone who would know what this sophisticated clientele would want. Edmond Jaeger was based in Paris, he had his shop, he was a watchmaker and a jeweller himself.

“He knew that people wanted something more sophisticated than a thick pocket watch. They were not very comfortable to wear, they wanted something more elegant. He knew the trends but he did not have the expertise to make what the clients wanted.”

Thus the collaboration between Edmond and Jacques-David LeCoultre, the founder’s grandson, was born, and brought about the name Jaeger-LeCoultre. Having already made huge strides in growth as a watch company - LeCoultre already employed 500 people by 1888 - it was from 1903 onwards that the company set out on its path towards worldwide fame.

It was in the 1920s that Jaeger-LeCoultre’s iconic wristwatches and clocks began to emerge. First was the Duoplan, a watch that catered to the fashion for small timepieces by allowing the movement, or the mechanical parts, to be on two levels, so the diameter could be smaller. Then, Atmos mantle clocks came into existence in 1928. To this day, they are habitually presented to the Swiss Government who will in turn present them to heads of states.

“We do not know what they plan to do with the clocks, but, for example we will later see a photograph of the clock with the President of the United States,” explains Marina.

Then in 1931 came perhaps one of Jaeger-LeCoultre’s best-known icons, the Reverso, a rectangular watch designed at the request of polo-playing British Army officers who wanted a timepiece that looked stylish but could survive the rigours of a polo match. The watch can literally be “reversed” with a mechanism which allows the wearer to turn the delicate face of the watch towards the back so there is less chance of damage.

In recent years, Jaeger-LeCoultre has shown that is unwilling to stand still in terms of horological development with Master Watchmaker Christian Laurent, who has been with the company for 40 years, overseeing ever more fascinating and complex adventures in haute-horlogerie. For example, the Master Grande Tradition Gyrotourbillon 3, unveiled at the equivalent of the World Expo of watchmaking, SIHH, held in Geneva in January.

To observe the watch, you get the sense that this is what 180 years of watchmaking history has led up to, as it is the jewel in the crown of the brand’s Tribute to Antoine LeCoultre Jubilee Trilogy. Its Flying Tourbillon, often considered the beating heart or equivalent of a pendulum, rotates or “gyrates”. The Flying Tourbillon, due to a feat of remarkable horological engineering expertise, appears without the usual supporting upper bridge, so the mechanism appears to float freely in its cage.

It comes as no surprise, when touring the factory, that the makers of these extraordinary examples of miniature engineering are considered the A-Team of their Manufacture, many with six years of training behind them, three years in apprenticeship and then three years training on the “Grand Complications” before they are considered competent in their craft. The task of producing the complication for the Gyrotourbillon 3, and other highly complicated watches, is carried out on the Manufacture’s highest floor, where the light is best.

Although much of the old-fashioned watchmaking furniture of old exists, particularly in the classroom that exists to give visitors an insight into the process, today, high-tech instruments are commonplace, with one room, dedicated to escapements, the part of the mechanism that produces and transfers energy to the watch movement, filled mainly with women who work all day at their microscopes, such is the minutely delicate precision of their work. However, it would appear that the structure of the Manufacture remains the same in some respects, with the larger less delicate pieces such as the outer cases being stamped and pressed into shape by technicians on the lower floors. Designers and engineers work in offices, pondering future timepieces and finessing current designs, in quieter parts of the building.

All in all, it Jaeger-LeCoultre seems to have cornered the market in blending the traditional practices of its watchmaking past with complex designs of the future. It seems likely that the brand will still be producing innovative but beautiful timepieces in another 180 years.

www.jaeger-lecoultre.com

TEXT: IMOGEN LILLYWHITE

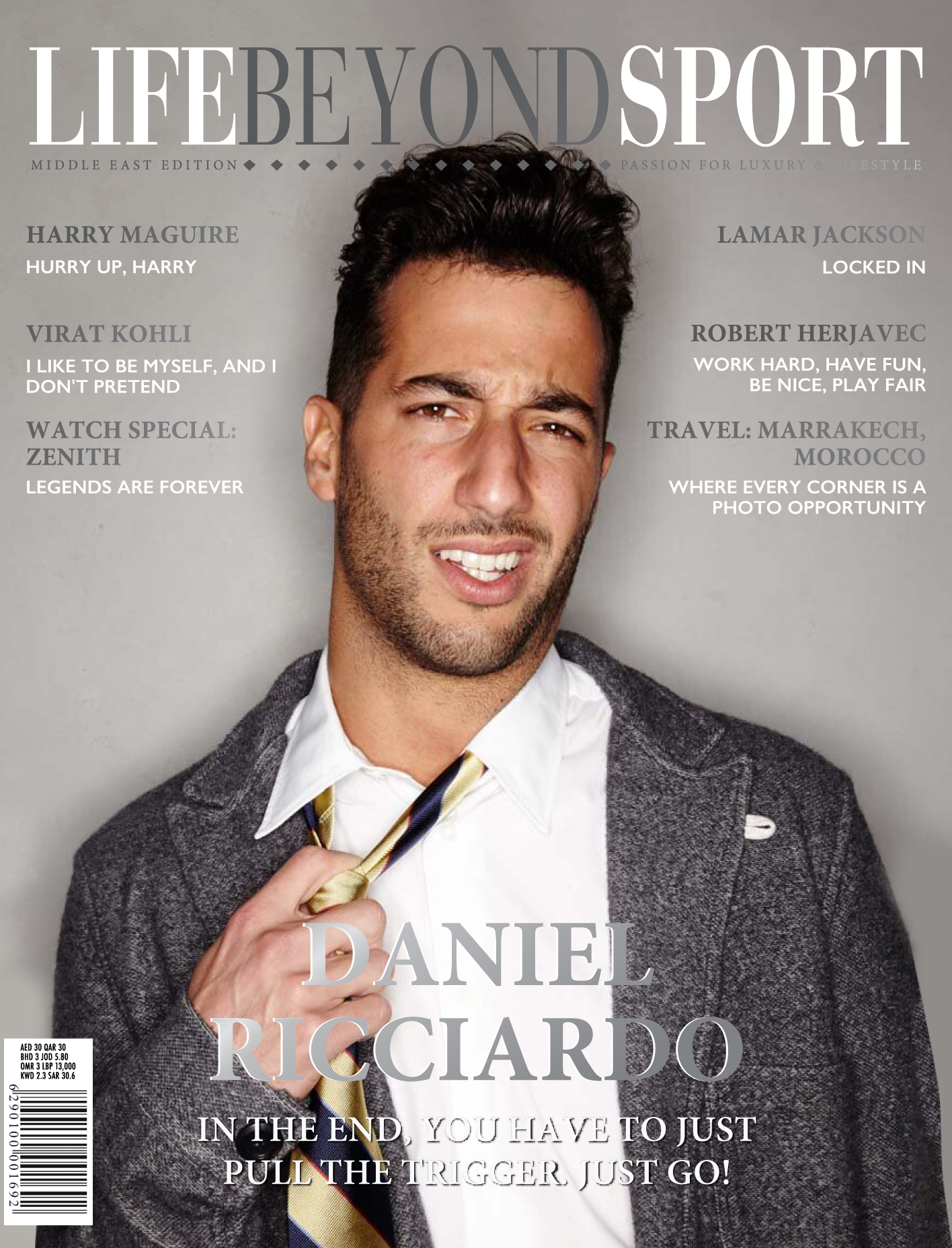

.jpg) Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.

Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.