As the first Tour winner after Lance Armstrong was stripped of his 1999-2005 titles in October 2012, Froome, who triumphed in 2013 and 2015, inspires admiration and accusations: is he a global superstar or another drugs cheat? This toxic suspicion ensures he navigates interviews with polite formality and remains something of a mystery.

Froome’s quiet dignity and manners do not prevent a militant minority believing his success is down to drugs. He has been drenched with urine at the Tour and spat at by fans. French journalists hurl relentless accusations.

‘It is hard not to take that stuff personally but I do get it,’ he says.

‘I can see how many times people have been deceived. But it is not easy to compartmentalise all that and not get hurt. Unfortunately a lot of cycling fans have been burnt in the past and it will take time for them to regain that trust.’

Froome was born in Nairobi on May 20, 1985. His English father, Clive, moved to Kenya to set up a holiday company. His mother Jane was born in Kenya to a couple from the UK. He grew up in an affluent suburb with his older brothers Jonathan and Jeremy (both now accountants) and enjoyed a vividly African childhood, exploring nature, getting chased by hippos and keeping pet pythons.

‘I lived a very outdoor life and my parents gave me independence. Because I experienced a lot from a young age I grew up much quicker.’

‘I lived a very outdoor life and my parents gave me independence. Because I experienced a lot from a young age I grew up much quicker.’ Froome was six when his parents’ holiday company collapsed and their marriage crumbled. By now his brothers were studying at Rugby School in Warwickshire but financial problems meant he remained in Kenya with his mother, who trained as a physio to make ends meet. He insists he is proud of his Kenyan upbringing but always felt British. He ate Sunday roasts and shepherd’s pies. At school he played rugby.

‘I grew up in a British family but just in a completely different setting away from Britain. And I was raised with strong British values and morals and beliefs.’

A sense of dual identity lingers today.

‘I certainly have different identities [British and Kenyan] but I think that is common today. The world is changing and it is quite a modern thing.’ He loved cycling in the Maasai territory of the Rift Valley, dashing past baboons and giraffe.

‘I had no knowledge whatsoever of the Tour de France. Cycling was about getting around on my bike and having fun. It was my freedom and my independence. It was only later when I saw the Tour on TV [at 17] that I realised there was this whole sport out there.’ A pivotal moment came when his mother approached the Kenyan cyclist David Kinjah at a local race and asked him to train her bike-obsessed son. Kinjah led a group of riders called the Safari Simbaz.

While Froome’s friends lounged around pools, he was chasing older riders along bumpy roads in the hills, often sleeping top to tail with Kenyan boys in Kinjah’s single-room, tin-roof home, after long rides. They called him ‘Murungaru’ (gangly kid). ‘

The Simbaz gave me raw passion for the sport. They taught me that it didn’t matter about having the best equipment because these guys were on a shoestring budget but still getting out there with six- or seven-hour rides on roads that were virtually non-existent.’

Living and training at altitude, where the body adapts to the thin air by producing more oxygen-carrying red blood cells, surely increased Froome’s stamina.

‘I think it has a lot to do with how I turned out. Especially if you draw comparisons with Nairo Quintana who was also born at altitude, in Colombia.’

After sending hundreds of emails to teams, in 2007 Froome moved to Europe to race for a special team of athletes from developing nations managed by the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), cycling’s governing body, in Switzerland, and the Konica Minolta pro team based in Belgium. Despite his obvious talent, he was tactically clueless. At one race he careered into a flower bed; at another he rode to the wrong finish line. He didn’t know how to brake safely on Alpine descents.

‘Most riders went to an academy or national-funded body in their teens but I missed that step so I was learning those things for the first time.’

In 2008 Froome began racing under a British licence. His motivations were both feeling British (‘There is no doubt in my mind where I stand in that regard’) and he knew Britain could offer more professional support. After racing for the Barloworld pro team between 2008 and 2009 he joined the newly formed, British-run Team Sky in 2010. His coaches couldn’t understand why he would impress in some races (fifth in the 2010 Commonwealth Games time trial) but fade in others. Then in late 2010 he was diagnosed with bilharzia, a waterborne parasitic disease, which he believes he caught while swimming in rivers or cycling through stagnant water in Kenya.

‘Bilharzia is a drain on your whole system. Who knows how long I had it for? There are millions of people in Africa living with bilharzia and they don’t know they have it. But for an endurance athlete it can have a big effect.’

Sceptics claim this is a convenient excuse for Froome’s rapid improvement, but bilharzia affects 250 million people worldwide and is second only to malaria among parasitic diseases. Could he have won the Tour with bilharzia?

‘No. Definitely not. Because we push ourselves so hard we get close to that line when your immune system can’t cope. That was always the tell-tale sign that something was wrong. Every time I felt competitive I would get a cold that put me back again.’

It took several doses of biltricide medication to cure him but Froome finally began to benefit from the advanced training methods promoted at Team Sky, cycling up a volcano in Tenerife, executing fitness-boosting threshold sessions (an excruciating 40 minutes of high effort), and performing ‘fasted rides’ (before breakfast) so his body was forced to burn fat.

Despite an impressive second place in the prestigious Vuelta a España race of 2011, Froome really came into the spotlight when he rode in support of Sir Bradley Wiggins in the 2012 Tour. On the controversial 11th stage Froome accelerated away from his teammate before being instructed over the team radio to return. Wiggins felt betrayed. Froome insisted he had the contractual right to fight for his own ranking after fulfilling his duties to Wiggins.

The two riders’ wives engaged in a brief Twitter spat. A fragile order was restored and Froome helped Wiggins to victory while finishing runner-up himself. But in 2013 he supplanted Wiggins as the team’s leader and stormed to his first Tour victory. After crashing out the following summer he won again in 2015.

‘The Tour is so brutal that some nights I have to sit in the shower because I can’t stand up. But you know the next morning you have to do another 150 miles.’ He burns up to 8,000 calories per day.

‘You turn yourself inside out for three weeks to stand on that podium. You think about all the hard work and sacrifices. It’s a whole mix of emotions.’ At his victory speech in 2013 Froome dedicated his win to his mother, who died in 2008, and insisted his victory would stand the test of time. He says he could never betray her memory by cheating.

‘Going back to those British values I was brought up with… I wish I could show everyone that this is the person I am and what they are accusing me of is just beyond me.’ Last month Froome was awarded an OBE, presented by the Duke of Cambridge.

Not all the attacks on Froome are personal. Team Sky is the most glamorous team in cycling, with a £25 million annual budget, big-name sponsors like 21st Century Fox, and world-class sports-science coaches and nutritionists. Resentment is inevitable. And as France hasn’t produced a Tour champion since 1985, pockets of the French media don’t appreciate les rosbifs dominating their race. But given cycling’s dark history, questions are not just fair but imperative.

In a bid for transparency Froome volunteered for independent physiological testing at the GlaxoSmithKline Human Performance Lab last summer, with the results published in Esquire magazine. The experts concluded that Froome’s V02 max of 88.2 was close to the ‘upper limits’ of human potential and, crucially, represented ‘a similar absolute aerobic capacity’ to another remarkable figure of 80.2 he had achieved in a test at the Swiss Olympic Medical Center in 2007. Put simply, his extraordinary engine was there nine years ago, but only through coaching and dedication (and dealing with bilharzia) did he reach his potential. Another secret behind his improvement was weight loss. Between 2007 and 2015 Froome dropped from 75.6kg to 67kg (about 11st 8lb to 10st 5lb).

This dramatically enhanced what is known as his ‘power-to-weight ratio’ – a key performance marker in mountain races, where gravity is the enemy. Every kilogram of bodyweight equates to carrying an extra bag of sugar up a mountain. Froome had effectively jettisoned 8.6 bags of sugar, making him lighter and faster.

‘Power-to-weight is so important in cycling. You want to trim your weight but you also need the power to perform in a bike race. It’s not easy. You have basically got to look at everything that passes your lips.’ Froome cut down on gluten, processed foods and sugar and ate lean protein, vegetables and quinoa.

His weight loss has been safely monitored by the team nutritionist.

‘There are times when you go hungry. But I know in the off-season I can have a pizza or some bread with my meal.’ Sport will always attract cheats but modern testing is robust. Froome has been tested up to 80 times each year, including three times in one day at the 2013 Tour.

‘Every day of your life, 365 days of the year, you have to let the drug-testing authorities know where you are,’ he says.

When contemplating Froome’s extraordinary journey from chasing the Safari Simbaz to winning the Tour de France, observers must choose between faith and doubt. But to equate success itself with guilt represents a harmful regression in which healthy scepticism has been twisted into darker cynicism. Science confirms Froome is a supreme athlete and his gifts can be credibly attributed to nature (living and training at altitude) and nurture (his strict training and diet).

Froome has demanded more drugs tests at training camps, even welcoming proposed night time tests at the Tour. Emma O’Reilly, Armstrong’s soigneur – the name given to cycling’s all-seeing masseurs – exposed his drug use. Froome’s soigneur David Rozman named his son after him. Such details prove nothing but they do provide perspective.

‘I have gone above and beyond what my rivals have done in terms of releasing physiological information and being open, but there comes a point where my job is to race my bike and not to go around pleasing doubters,’ says Froome.

‘I meant those words that I said on the podium, that I would never dishonour the yellow jersey. And I know that in 10, 20, 30 years from now my results will still stand.’

TEXT: MARK BAILEY // PHOTOGRAPHY: FRANCOIS DE LANNOY

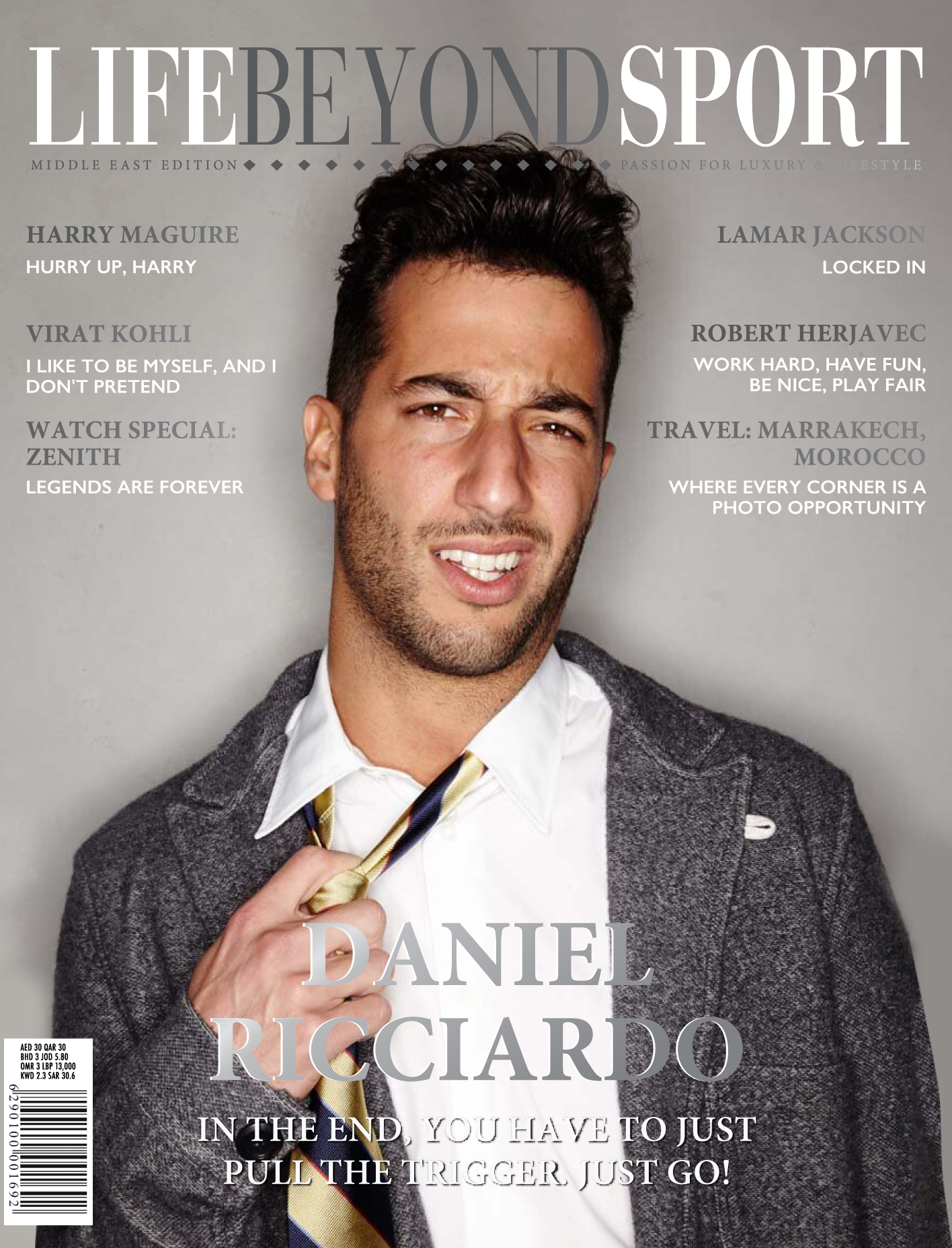

.jpg) Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.

Life Beyond Sport magazine is a pioneering publication that breaks through the traditional barriers of men’s lifestyle magazines by smoothly combining a man’s love of sport with his passion for the finer things in life. The magazine contains a range of features, interviews and photo-shoots that provide an exclusive insight into the sportsman’s lifestyle. Only in Life Beyond Sport will you find the biggest names from the worlds of Football, Tennis, Formula 1, Golf, Polo and more.